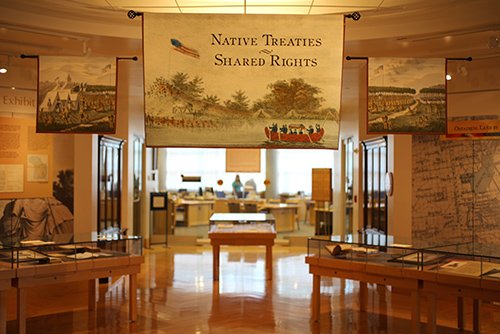

Native Treaties - Shared Rights Exhibition

What is a Treaty?

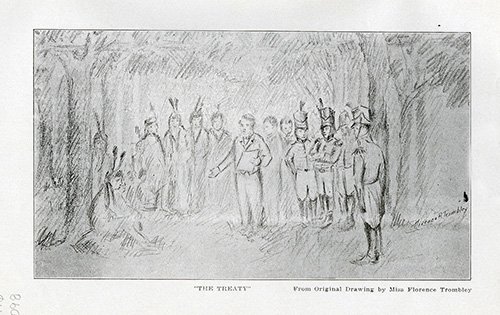

The treaties signed by the United States Government and various Tribal Governments created legally binding agreements between nations. In return for concessions from the Tribal Governments, usually land, the United States Government was obligated to provide the signers’ nation with compensation. Compensation might include money, services, reserves of land, or rights. Some of these obligations were one-time occurrences while others, particularly the rights preserved or granted in a treaty, were often perpetual. American Indian treaty signers, as well as all of the members of their community and all their descendants, hold these rights.Article 1, Section 8 of the United States Constitution vested in the Federal Government the responsibility to develop relations with Tribal Governments. Section 8 states Congress shall have the power:

To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes;

The clause established a government-to-government relationship between the United States and the various Tribal Governments and created the legal framework for the many treaties that would follow.

Alternatives to Treaties

War was the only real alternative to treaty negotiations. The decision by the United States to negotiate with Tribal Governments rather than wage war was based on a mixture of morality and experience.The United States experience in Indian Wars demonstrated that, generally, the outcome of war was uncertain, the expense was greater than that involved in negotiations, and the price in lives was unacceptable. In 1790 and 1791 the United States sent soldiers into the Old Northwest Territory (what would become the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and a part of Minnesota) to confront Tribal Governments. Both expeditions were defeated by warriors representing a coalition of Tribal Governments. A third U.S. expedition was organized in 1793 and a year later fought a coalition of warriors near what is today Toledo, Ohio. The Battle of Fallen Timbers was a victory of the U.S. forces.

What made the battle important was the diplomatic outcome. The British had encouraged Tribal Governments to fight the United States and offered support to a Tribal military alliance. However, shortly after the Battle of Fallen Timbers, the British garrison in nearby Fort Miami refused temporary refuge and badly needed gun powder to the retreating tribal warriors. This led many of the warriors and their leaders to question Britain’s commitment and caused the Tribal alliance to shatter. The Battle of Fallen Timbers ended large-scale, armed Tribal resistance in the Old Northwest Territory until the War of 1812, but the experiences of 1790-1794 made the costs of war against Native Americans very clear to the Federal Government. Whenever possible, negotiation was preferable to war.

Obtaining the Land

Many reasons underlie the decision by the United States to negotiate with Tribal Governments to obtain land. Not only did the Constitution create a legal mandate to negotiate, there was also the moral belief that the Tribes either owned the land

or held at least some type of title to it. The final reason was the pragmatic observation that the cost of war was greater than the money needed to negotiate and implement treaties.

Many reasons underlie the decision by the United States to negotiate with Tribal Governments to obtain land. Not only did the Constitution create a legal mandate to negotiate, there was also the moral belief that the Tribes either owned the land

or held at least some type of title to it. The final reason was the pragmatic observation that the cost of war was greater than the money needed to negotiate and implement treaties. Many treaties with various Tribal Governments transferred the land which today is Michigan from tribal control to the United States. These treaties remain in force, guaranteeing rights and privileges to citizens of both the United States and citizens of the Tribal Governments which signed the documents.

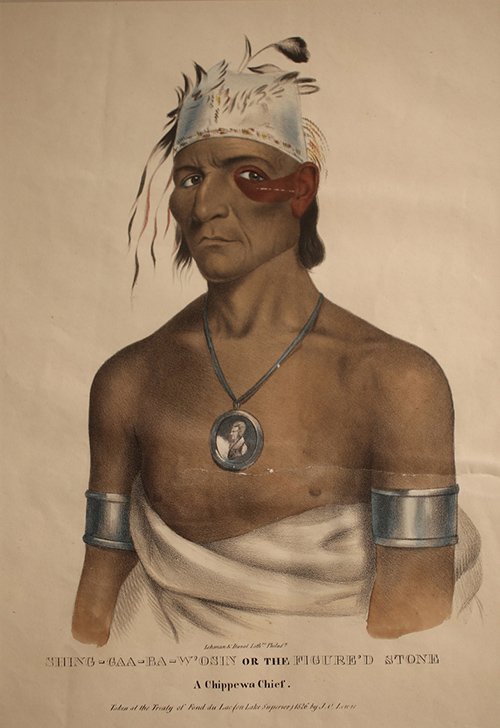

From the Native American perspective, the United States' endless quest for land left no room for Native government or society. This realization was dramatically acted out in 1826. While attending treaty negotiations at Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin (Figured Stone) saw a United States negotiator sitting on a stump. He sat on the stump very close to the negotiator, practically pushing him off. The perplexed negotiator moved to another stump, and Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin followed him and did the same thing. Eventually, he pushed the man onto the ground. Then he said:

Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin’s speech was, in many ways, a counterpoint to the career of Lewis Cass. Cass negotiated twenty treaties while he served as the governor of Michigan Territory, from 1815 to 1830. He oversaw the 1819 Treaty of Saginaw, which brought about the surrender of nearly a third of the lower peninsula of Michigan to control of the United States, and he represented the U.S., as commissioner, at the treaties of Prairie du Chien 1825, Fond du Lac 1826, and Butte des Mort 1827 (the three “Augustic Treaties,” so named because they occurred in three successive years in August).

In several articles that appeared in the North American Review in the 1820s, Cass advocated moving all tribes to lands lying west of the Mississippi River. Cass built his case around a sentimental racism, shared by many, that assumed the sad but inevitable disappearance of Native populations as white settlements advanced westward. This widely-held “extinction discourse,” writes Patrick Brantlinger, “served as the ideological basis for the passage of the Indian Removal Act.”

Removal sparked debate in the press and in the Congress. An anti-removalist movement formed. It would be the seedbed of other nineteenth century reform movements. If Cass served as the spokesman for removal in the national press, Jeremiah Evarts, the Secretary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, served as an articulate spokesman against removal. Evart’s anti-removalist essays appeared in 1829 in the pages of the National Intelligencer, under the pseudonym, William Penn. In the words of one historian, Evart’s William Penn Essays “remain an extraordinary compendium of arguments on behalf of Indian rights and on the obligation of the United States Government to protect them.”

In the court of public opinion, however, Cass and the others who supported removal clearly won the argument. Removal became government policy.

Michigan Treaties

Treaties Conveying Land That Would Become Michigan  The following treaties between Tribal Governments and the United States Government conveyed land to the U.S. which became part of Michigan:

The following treaties between Tribal Governments and the United States Government conveyed land to the U.S. which became part of Michigan:

Read more about the following treaties.

• Fort Greenville, Ohio, August 3, 1795

• Detroit, November 17, 1807

• Foot of the Rapids, September 29, 1817

• St. Mary’s,

Ohio, September 20, 1818

• Saginaw, September 24, 1819

• Sault Ste. Marie, June 6, 1820

• L’Arbre Croche & Michilimackinac, July 6, 1820

• Chicago, August, 29, 1821

• St. Joseph,

September 19, 1827

• Carey Mission, September 20, 1828

• Chicago, September 27, 1833

• Washington, March 28 & May 9, 1836

• Cedar Point, September 3, 1836

• Detroit, January 14, 1837

• La Pointe, October 4, 1842

• Detroit, July 31 & August 2

(two separate treaties), 1855

• Isabella Reservation, October 18, 1864

• Land was also conveyed by Congressional

Acts in March 3, 1843 & June 22, 1874.

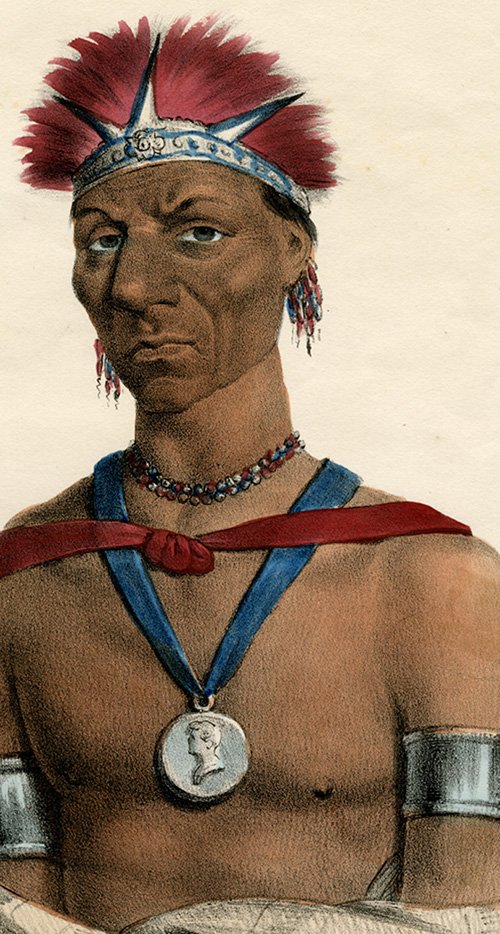

Peace Medals

Peace medals were a symbol of treaty negotiations, and an item often worn by Native American leaders as an object of adornment.

Peace medals were a symbol of treaty negotiations, and an item often worn by Native American leaders as an object of adornment.

Peace medals symbolized friendship and alliance between the Tribes and the U.S. Government. By honoring Tribal

leaders with peace medals, U.S. treaty commissioners were following a practice established by the Spanish, French, and British before them.

Issuing medals became a permanent feature of treaty negotiations. Made of silver, or silver

and copper, of high quality, the medals were generally struck in three sizes. Principal village leaders received large medals; less renowned warriors received smaller medals. The U.S., at times, was accused of creating “medal chiefs.”

Medals were issued not only when treaties were signed but also when important Tribal leaders visited Washington, D.C., or when U.S. officials made tours through Indian country. Esteemed by their recipients, peace medals were often handed down

from generation to generation.

Francis Paul Prucha, has written:

(Francis Paul Prucha, Indian Peace Medals in American History Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1971, xiii-xiv.)

Rules were established for the distribution of these medals. In 1829, treaty commissioners Lewis Cass

and William Clark created the following rules:

Rules were established for the distribution of these medals. In 1829, treaty commissioners Lewis Cass

and William Clark created the following rules:- They will be given to influential persons only.

- The largest medals will be given to the principal village chiefs, those of the second size will be given to the principal war chiefs, and those of the third size to the less distinguished chiefs and warriors.

- They will be presented with proper formalities, and with an appropriate speech, so as to produce a proper impression upon the Indians.

- It is not intended that chiefs should be appointed by any officer of the department, but that they should confer these badges of authority upon such as are selected or recognized by the tribe, and as are worthy of them, in the manner heretofore

practiced.

- Whenever a foreign medal is worn, it will be replaced by an American medal, if the Agent should consider the person entitled to a medal.

Who Owned the Land?

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the descendants of European settlers asked a curious question: who first owned the land?Native Americans had trouble understanding why the question was asked. They were here first. They owned the land. Nor where they were anxious to sell it. As Saginaw Ojibway leader Ogemagigido (1795-1840) said:

We are here to smoke the pipe of peace, but not to sell our lands. Our American Father wants them. Our English Father treats us better. He has never asked for them. Your people trespass upon our hunting ground. Our land melts like a cake of ice. Our possessions grow smaller and smaller. The warm wave of the white man rolls in upon us and melts us away. Our women reproach us. Our children want homes. Shall we sell from under them the spot where they spread their blankets? We have not called you here.

During and shortly after the American Revolution, the colonists usually agreed that the land first belonged to the Indians. As John Adams wrote, with more than a bit of ahistorical positivism; “Our ancestors were sensible of this [Native ownership of the land], and therefore, honestly purchased their lands of the natives.” But his son, John Quincy Adams, became part of a legal movement to reinterpret the question. He conceded that American Indians owned the land they lived on or farmed. But lands that Native Americans neither lived on nor farmed, which he believed to be the great majority of the continent, he believed was not owned by the Indigenous people. J.Q. Adams asked rhetorically, “Shall the lordly savage not only disdain the virtues and enjoyments of civilization himself but shall he control the civilization of a world?” His answer was that this “unused” land belonged to the United States.

In 1823 this theory was accepted, in a modified form, by the Supreme Court. It remains a part of contemporary American law.

For a more extensive essay regarding the policies of the U.S. Government toward Native American residency on the land, please read the Brief History of Land Transfers Essay.

Honoring Treaty Agreements about Land

Despite treaty obligations, the U.S. Government usually looked away when tribal land was taken either illegally or unethically. Examples of this occurred in Michigan’s Isabella County.The 1918 History of Saginaw County told how a lawyer, aware of where and when federal Indian Commissioners would meet Anishinabek tribal members to transfer land titles, secretly rifled through the Commissioners’ papers, copied the titles, and identified the best timber areas. He then met with the Indians who owned the land. “He knew many of the Indians personally, and it was not a difficult matter to get them 'feeling good,' and then … induce them to sign away their timber rights.”

In 1953, the United States Indian Claims Commission found, "The evidence shows that whites, in devious ways, obtained timber from Indian lands in the Isabella Reservation."

In 1953, the United States Indian Claims Commission found, "The evidence shows that whites, in devious ways, obtained timber from Indian lands in the Isabella Reservation."Learn more information about land dealings on the Saginaw Chippewa Reservation.

Hunting and Fishing Rights in Treaties

Treaties signed in 1820, 1836, and 1855 preserved for five Michigan-based Tribal Governments pre-existing fishing rights in the Great Lakes. In 1973, the State of Michigan enacted laws limiting commercial fishing and applied these laws to Tribal members.Several Tribes sued the State. The Tribes argued 1) that they had historically fished the Great Lakes before treaties had been signed, 2) through the treaties they had retained the right to fish, and 3) that the Tribes had actively and continually fished commercially since the treaty signing. In 1979, a federal judge found in favor of the Tribes. The treaties preserved their rights, and the State of Michigan could not regulate fishing conducted by Tribal members.

Learn more about fishing rights

Michigan State Law Cannot Change a Treaty

After the founding of the United States, many states sought Tribal land for white settlement.Georgia was particularly aggressive in doing so. In the 1820s, Georgia passed a series of laws which asserted that the State owned the Cherokee nation’s land and could apply state law on it. In every way possible Georgia’s government attempted to drive the Cherokee westward.

In Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the U. S. Supreme Court ruled that Georgia had acted illegally. Chief Justice John Marshall ridiculed the “extravagant and absurd idea, that the feeble settlements made on the sea coast” by Europeans gave them the right to govern American Indians or take their land. European settlers had only the right to purchase “such lands as the natives were willing to sell.” Marshall would ultimately conclude, “the Cherokee nation, then, is a distinct community occupying its own territory, with boundaries accurately described, in which the laws of Georgia can have no force.”

Previous decisions by Marshall had emphasized the authority of the Federal Government over Tribal Governments. A year earlier he found that Tribal Governments were “domestic dependent nations,” and “their relation to the United States resembles that of a ward to his guardian.” In 1823, he had ruled that first possession of the land gave neither Tribal Governments nor individual American Indians land ownership as it was defined by U.S. law. American Indians had a “right of occupancy” that should be recognized and legally obtained from them prior to white settlement, but the land was legally owned by the U.S. Government.

Particularly in the nineteenth century, the collective impact of these rulings was to make it difficult if not impossible for Tribal Governments or individual American Indians to find justice in the courts.

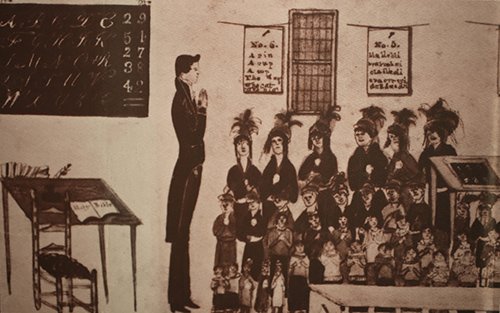

Education In Treaties

Most

treaties included provisions for the education of tribal members. Many

tribal leaders realized the need for European education to sustain their

culture in a future that would include large numbers of non-Native

people.

Most

treaties included provisions for the education of tribal members. Many

tribal leaders realized the need for European education to sustain their

culture in a future that would include large numbers of non-Native

people.

In 1832, Shingwaukonce, who lived at times on both the American and Canadian sides of the St. Marys River and signed treaties with both the United States and British Canada, brought missionaries and teachers into his Tribe. Shingwaukonce sought Western knowledge but saw the educational process as Native controlled, with Western education supplementing, rather than replacing, his Tribe’s existing way of life.

As Shingwauk put it, his hope was that:

. . . before I died I should see a big teaching wigwam built at the Garden River where children from the Great Chippeway Lake would be received and clothed, and fed, and taught how to read and how to write; and also how to farm and build houses, and make clothing; so that by and bye they might go back and teach their own people.

In contrast to most nineteenth-century Christian missionaries and government officials, who saw education as a means to “civilize” American Indians and integrate them into American culture, Shingwaukonce and Shingwauk both emphasized that education should be tribally controlled and integrate Western knowledge to serve Tribal objectives.

Education Beyond Treaties

Exactly what educational opportunities were granted to Tribal Governments and their citizens were often subject to differing interpretations. In the 1960s, several people concluded that a treaty signed in 1817 required The University of Michigan to grant free tuition to some American Indians. The treaty read, in part:Some of the Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potawatomy tribes, being attached to the Catholic religion, and believing they may wish some of their children hereafter educated, do grant to the rector of the Catholic church of St. Anne of Detroit [specific land], for the use of the said church, and to the corporation of the college at Detroit, for the use of the said college, to be retained or sold, as the said rector and corporation may judge expedient.

In 1974, a federal court ruled that while the treaty might create a moral responsibility to educate Tribal members, it did not create a legal right.

Supplementing Treaties: Higher Education as a Moral Right

A

sense that treaties morally obliged Michigan to educate its American Indian citizens, led to action in the Michigan legislature. A Detroit News story published on May 21, 1976 summed up this sentiment:

A

sense that treaties morally obliged Michigan to educate its American Indian citizens, led to action in the Michigan legislature. A Detroit News story published on May 21, 1976 summed up this sentiment:. . . the history of Michigan and the country is replete with promises to Indians, including a guarantee to Michigan Indians of state supported education in return for land already transferred to the state. Without ever passing a law to guarantee the education the state in effect has reneged on its promises made in early treaties.

While the appeals of the 1974 The University of Michigan decision proceeded through the courts, discussions about the issue were also occurring in the state legislature. Legislators from Detroit, particularly Jackie Vaughn, put forward legislation on the subject using a Minnesota program as a model.

Vaughn, one of only a handful of African-Americans legislators at the time, saw the bill as a way to introduce the idea of affirmative action:

. . . there were those [who] were keen toward this, in terms of other minorities. I don’t have to tell you, if I’d have tried to say ‘I want to introduce a bill for all Afro-American free tuition’ I would have been laughed out of existence. But for Native Americans they were sympathetic, and I recognized that.”

Vaughn recalled, though, that not everyone saw it his way. “There were a couple of them [Black members of the House] against it, because ‘why should they have it when we don’t have it?’” Other members of the legislature

also opposed the bill. Senator Thomas Guastello argued that there were higher priorities for limited educational funds. Responding to the statement that the U.S. “had robbed the Indians of their land and failed to educate their children,”

Guastello said he was “tempted to say that if the Indians don’t like it here, they can go back where they came from.”

In 1976, Vaughn’s bill became law: Public Act 174 created the Michigan Indian Tuition Waiver program,

granting Michigan’s Native American citizens free tuition at the state’s publicly-funded colleges and universities.

K-12 Education of Native Americans

In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, primary education was an important goal for many Tribal Governments. Tribal leaders recognized a need for members who could read and write English, and who could serve as informed ambassadors between their

Tribes, the Federal Government, and white society.

By 1855, missionaries were operating primary schools at various Anishinabe settlements. After the Treaty of 1855, the Federal Government began to directly operate primary schools for Michigan

Indians.

The Anishinabek usually supported sending their children to these day schools, but the U.S. Government found them unsatisfactory. As early as 1866, Michigan Indian Agent Richard Smith requested permission to build a boarding school. His

goal was to separate the children from their families and their community to more fully and quickly integrate them into white society. After the Civil War, this became the basic goal of the U.S. Government’s Indian education program, a goal

never acquiesced to by the Anishinabe community.

In 1893, a Native American Boarding School was opened in Mt. Pleasant, where it continued to operate until 1933. By 1911, the campus had grown to accommodate up to 375 students. The school was run according to military principles and only English was spoken. The school never accomplished its goal of erasing Anishinabe culture among the community’s children; in fact it helped create a new spirit of unity among Anishinabe children through shared experiences and a common history. The school also gave new generations of Tribal leaders skills to better cope with the U.S. Government and white society.

Students lined up in front of the boarding school.