Other Commercial Ventures

Commercial and Overseas Sales

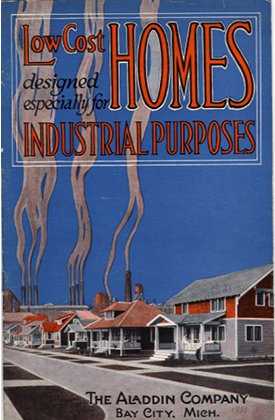

Although

the Sovereign Brothers initially sold homes to individuals, they soon

realized that a secondary commercial market existed. Particularly in

remote areas, "company towns" constructed at the firm's expense were

common. By 1916 Aladdin had made several large group sales to

manufacturers seeking housing for workers. With America's entry into

World War I demand for worker housing soared. Many companies found that

Aladdin homes, with their low prices and easy assembly, well met their

needs.

Although

the Sovereign Brothers initially sold homes to individuals, they soon

realized that a secondary commercial market existed. Particularly in

remote areas, "company towns" constructed at the firm's expense were

common. By 1916 Aladdin had made several large group sales to

manufacturers seeking housing for workers. With America's entry into

World War I demand for worker housing soared. Many companies found that

Aladdin homes, with their low prices and easy assembly, well met their

needs.

Perhaps the most storied of Aladdin's group sales was made by the Austin Motor Company in Birmingham, England. In November 1916 Austin purchased two hundred modified "Chester" houses. The houses were loaded on the SS Headley, but were lost when the ship was sunk by a German submarine. In March 1917 a second shipment of two hundred homes was sent from New York, this time arriving safely in England. By June 1917 all two hundred homes had been erected. These homes still stand in Birmingham, an isolated island of Midwestern American architecture dropped into the British countryside. The homes narrowly survived German bombs during World War II. Today they are listed on the British Historic Register. A second overseas venture occurred in 1918 when an abridged version of the Aladdin catalog was printed in French and was distributed in Paris. The French venture, however, apparently proved unprofitable.

Hoping to stimulate more group sales in the United States, in 1920 and again in 1921 Aladdin published a specialized "Industrial Housing" catalog. The 1920 catalog featured the homes purchased by the Austin Company as well as those purchased by DuPont, and argued that Aladdin homes had met the needs of these two companies as well as over three hundred other firms whose names were printed in the catalog.

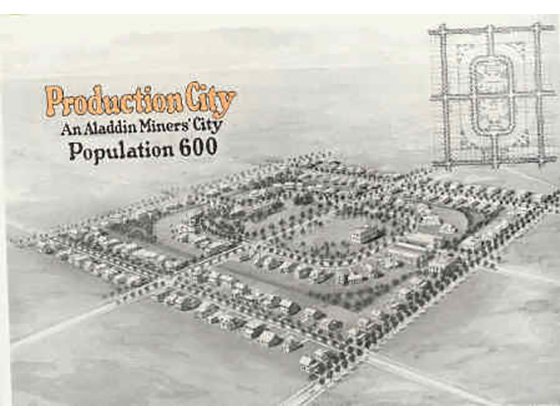

The 1920 catalog offered six complete "cities." The

cities included water treatment plants, lighting systems, and even

landscape plantings for streets. The cities ranged in size from the 300

person "Bessemer" to the 274 acre, 3,000 strong "Sovereign City."

The 1920 catalog offered six complete "cities." The

cities included water treatment plants, lighting systems, and even

landscape plantings for streets. The cities ranged in size from the 300

person "Bessemer" to the 274 acre, 3,000 strong "Sovereign City."

It

is unlikely the Aladdin ever actually sold a complete city. Aladdin had

sold all of the elements included in these cities to various corporate

and governmental customers, but they never seem to have sold an entire

city package to one customer. Perhaps recognizing this fact, the 1920

catalog did not really describe the city packages in any detail but

rather quickly moved from the full size cities to describe a wide

variety of individual structures for sale. Most prominent were

forty-eight homes; mostly small, low-cost models advertised as "worker"

homes.

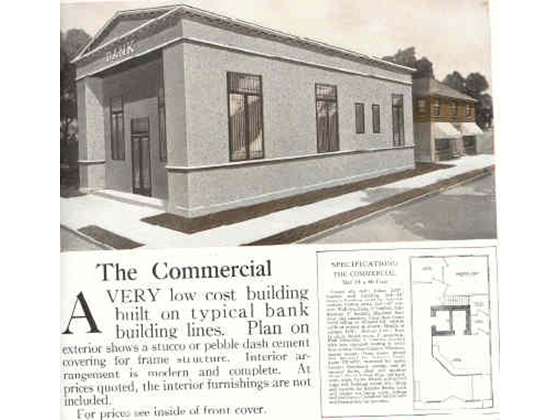

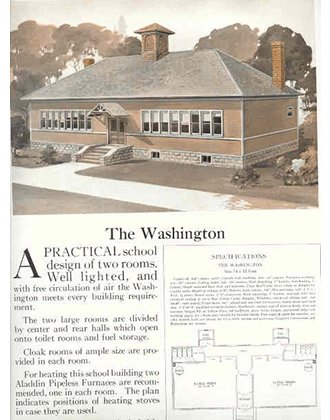

In addition the catalog offered a number of community

buildings such as a hotel, dining hall, boarding house, general store,

bank, warehouse, school, and church.

In addition the catalog offered a number of community

buildings such as a hotel, dining hall, boarding house, general store,

bank, warehouse, school, and church.

The 1921 catalog was less

grand but more accurately reflected Aladdin's market. The industrial

cities were gone and the focus was on inexpensive, worker homes. These

ranged from the "Gem," a very modest one hundred sixty square foot, two

room structure, through nine other structures, the largest being the

four room Hecla, a 784 square foot dwelling. The modest character of

these ten houses was indicated by their small size and lack of indoor

plumbing. Most of the community buildings were also gone, with only a

boarding house, bunk house, and dining hall available.

Although

Aladdin continued to sell groups of homes to various customers for many

years its effort to establish an industrial catalog was unsuccessful.

The 1921 industrial catalog was the last of its kind. Thereafter Aladdin

relied on its annual homes catalog for both individual and group sales.

Although

Aladdin continued to sell groups of homes to various customers for many

years its effort to establish an industrial catalog was unsuccessful.

The 1921 industrial catalog was the last of its kind. Thereafter Aladdin

relied on its annual homes catalog for both individual and group sales.

Military Housing

During World War I

Aladdin realized that its assembly techniques were well suited to

standardized military housing. On April 26, 1917 the Aladdin Company

received a letter from the military asking the firm to come to Fort

Snelling, just outside St. Paul, Minnesota, and erect a camp for 9,000

soldiers. The letter promised a formal contract would follow but

requested construction to begin at once. Apparently the Sovereign

brothers rapidly modified pre-existing building plans sold for

agricultural settings to meet the military's need. The firm erected the

camp in twenty-six days and completed the job three weeks before a

contract for it was signed.

During World War I

Aladdin realized that its assembly techniques were well suited to

standardized military housing. On April 26, 1917 the Aladdin Company

received a letter from the military asking the firm to come to Fort

Snelling, just outside St. Paul, Minnesota, and erect a camp for 9,000

soldiers. The letter promised a formal contract would follow but

requested construction to begin at once. Apparently the Sovereign

brothers rapidly modified pre-existing building plans sold for

agricultural settings to meet the military's need. The firm erected the

camp in twenty-six days and completed the job three weeks before a

contract for it was signed.

These same plans for group housing seemed to have been dusted off during the 1930's when Aladdin marketed military-style housing facilities to the Civilian Conservation Corp, which was establishing military-like camps across rural America. As in the 1920's the company produced special advertising material for these products and did not include them in their annual homes catalog. However, unlike the elaborate industrial catalogs of 1920 and 1921, Aladdin marketed the structures through small flyers and other inexpensive media.

During World War II Aladdin again turned to selling housing for the military. A typical product, touted in a four page advertising flyer published in red, white, and blue, was Aladdin's "fully demountable" five man huts.

The flyer promised that five enlisted men could erect the structure in 75 minutes and take it down in 32 minutes. Aladdin claimed it could manufacture one hundred of these huts a day. As early as 1942 Aladdin had $1.8 million in government contracts, with an additional $820,000 worth of military work in 1943.

Apparently after the close of World War II Aladdin ceased manufacturing barracks, mess halls, and other structures of this type.

Summer Cottages

Because the

company's first homes were very small, many were purchased by affluent

customers as summer cottages. Making the most of this, in 1908 Aladdin

printed a four page "Summer Cottages" flyer. Three cottages, styles "B",

"D", and "F", were offered, along with a "dwelling house" measuring

twenty by thirty-six feet.

Because the

company's first homes were very small, many were purchased by affluent

customers as summer cottages. Making the most of this, in 1908 Aladdin

printed a four page "Summer Cottages" flyer. Three cottages, styles "B",

"D", and "F", were offered, along with a "dwelling house" measuring

twenty by thirty-six feet.

Cottages became a steady market for Aladdin. In 1928, for example, the firm sold 144 summer homes. Beginning in 1909, summer houses were incorporated into the closing pages of Aladdin's annual homes catalog. Cottages would be a regular feature of Aladdin's annual homes catalog until 1948. In some years, such as 1915, 1923, and 1928, small, twelve to sixteen page specialty publications were issued featuring the summer cottages found in the pages of the annual catalog.

Although Aladdin did not specifically market cottages during the 1950's, apparently some of their smaller homes were purchased for vacation get-aways. In 1960 the firm issued a small "Vacation Homes" catalog that featured these less expensive homes. This represented the firm's last specific attempt to target sales for summer residences.

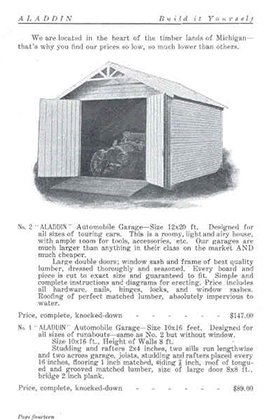

Automobile Garages

The small size of

many of Aladdin's buildings made them easily marketable as automobile

garages. Like many other "side line" structures, a small number of

garages regularly appeared in the back pages of the annual homes

catalog. After World War II the space devoted to garages in the catalog

declined. The 1961 catalog was the last to offer a garage to the public.

The small size of

many of Aladdin's buildings made them easily marketable as automobile

garages. Like many other "side line" structures, a small number of

garages regularly appeared in the back pages of the annual homes

catalog. After World War II the space devoted to garages in the catalog

declined. The 1961 catalog was the last to offer a garage to the public.

Agricultural Buildings

Prior to World War I Aladdin sold, in addition to houses, a number of agricultural buildings. In 1914 a sixteen page "Farm Building" catalog offered farmers barns, dairy barns, hog houses, sheep folds, poultry houses, milk houses and granaries. In 1917 Aladdin's Canadian subsidiary offered a second farm catalog. As with other specialty structures, specific buildings were also featured in the back pages of the annual homes catalog. Agricultural buildings last appeared in the Aladdin catalog in 1919.

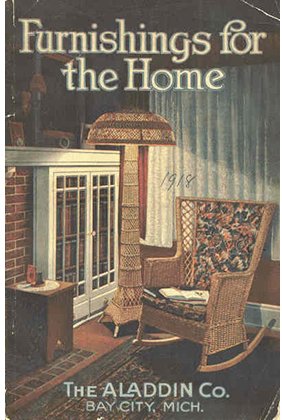

Home Furnishings

Beginning in 1914 Aladdin published a separate Homecraft Market Place catalog.

Promising to cut out the "middle man's" profit, the catalog claimed to

deliver a $1.00's worth of goods for only 60 cents. Prior to the

publication of the first Homecraft catalog, Aladdin had offered a variety of "additional" items in its annual homes catalog. The Homecraft catalog simply expanded an existing practice within the firm.

Beginning in 1914 Aladdin published a separate Homecraft Market Place catalog.

Promising to cut out the "middle man's" profit, the catalog claimed to

deliver a $1.00's worth of goods for only 60 cents. Prior to the

publication of the first Homecraft catalog, Aladdin had offered a variety of "additional" items in its annual homes catalog. The Homecraft catalog simply expanded an existing practice within the firm.Many of the products offered in these catalogs represented items that would otherwise be bundled into Aladdin houses. Products such as furnaces, kitchen cabinets, or electrical lighting fixtures apparently came straight from the homes Aladdin sold. Other items went farther afield. Furniture, rugs, dishware, vacuum cleaners and similar items clearly moved the company into a position that went beyond simply using pre-existing inventory. As the company expanded from hardware to furnishings, the Homecraft

catalog became a more direct challenge to the catalog merchandising operation of Aladdin's chief rival in the pre-cut home market, Sears. Aladdin continued issuing a "Furnishings" catalog, sometimes under different titles, for several years. The last large catalog was printed in 1918.

Apparently the enterprise was not sufficiently successful to justify continuing to publish a separate catalog. Various items that would have previously appeared in the Furnishings catalog, however, continued to be found in Aladdin's annual homes catalog for many years. Small twelve to sixteen page specialty catalogs of furnishings would also appear intermittently throughout the 1920's.

In the 1960's, the company tried once again to diversify by selling related items to its home buyers. In 1963 the twenty-eight page Aladdin's Shopper appeared. It offered consumers a wide range of products including a "cribbage cocktail table," 1/4 inch electric drills and other power tools, West Bend appliances, and Lionel trains.

Real Estate Speculation and Aladdin City, Florida

For many years the Sovereign Brothers not only sold homes to individuals but also dabbled in Bay City area real estate. It appears that they often purchased undeveloped lots and erected individual homes or small groups of homes for sale. The Sovereign's most extensive real estate speculation, however, was Aladdin City, Florida. In 1926 the brothers obtained a large parcel of land located twenty miles south of Miami. On it they began to build a Moorish accented city that was likely made up primarily of buildings found pictured in the cities featured in the 1920 industrial catalog. The development was, apparently, an initial success.

Unfortunately for the Sovereigns, the Florida real estate boom, which had seen real estate prices in cities like Miami climb twenty-fold in six short years, collapsed in the Depression of the 1930s. Its end was particularly hard on late investors. The Sovereigns, and other Florida real estate speculators, were forced to liquidate their now steeply discounted Florida land holdings on the best terms they could negotiate, usually considerably below what they had paid. Having rid themselves of Aladdin City, the Sovereigns never again launched a major development. It has been reported that Aladdin homes continued to be inhabited in the former Aladdin City until 1994, when the last of the structures fell victim to a hurricane.

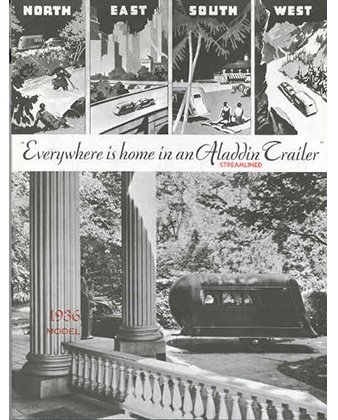

Aladdin Trailer

Introduced in 1934 the Aladdin "streamlined" trailer represented, according to the company's 1936 literature, "the natural evolution of the modern trend toward living on wheels." Aladdin stressed the durability of

its trailer as well as its aerodynamic design. The major selling point, however, was the "luxurious conveniences" and "beautiful, durable equipment." A complete kitchen "wholly concealed" in cabinets, were complimented by a folding table and a "tapestry

covered, daytime davenport seat and back" that converted into either two twin beds or a full bed. The sleeping arrangements could also be modified to create two bunk beds, sleeping four.

Introduced in 1934 the Aladdin "streamlined" trailer represented, according to the company's 1936 literature, "the natural evolution of the modern trend toward living on wheels." Aladdin stressed the durability of

its trailer as well as its aerodynamic design. The major selling point, however, was the "luxurious conveniences" and "beautiful, durable equipment." A complete kitchen "wholly concealed" in cabinets, were complimented by a folding table and a "tapestry

covered, daytime davenport seat and back" that converted into either two twin beds or a full bed. The sleeping arrangements could also be modified to create two bunk beds, sleeping four.The Aladdin trailer represented the company's most radical departures from the firm's traditional area of expertise organized around pre-cut buildings or house-oriented products. The Sovereign brothers willingness to experiment in this very different arena may have been the result of the abysmal home sales that effected the entire housing industry during the 1930's. The situation was so bleak that Aladdin's chief competitor, Sears, would abandon the pre-cut housing market during this decade, never to return. Unfortunately for Aladdin attempt to expand outside of the housing industry, the basic problem was not the lack of consumer interest in its pre-cut houses but the general economic situation. The trailer, like most everything else in the 1930's, sold poorly. Its production was thus short-lived.