Maureen Hathaway Michigan Culinary Archives - Exhibition Catalog

Through the generosity of Maureen Hathaway, the Clarke Library holds one of the largest collections of Michigan cookbooks in the state. Cookbooks were once thought of as ephemeral publications; books of little value to anyone other than a person seeking a banana-nut bread recipe. Food, however, plays a large part in every person's life. The customs that surround food; its preparation, how it served, and when it is served, are often part of the social fabric that knit together individuals, families, communities, and nations.

Historians have discovered that food unites us, divides us, and often defines us. Because of this culinary history has become a rich resource increasingly used by social historians as a tool through which to understand local, regional, and even national history. Because of the importance of culinary history the Clarke Library is extremely pleased to make this collection available to the public.

To find books from the collection please search the words “Maureen Hathaway” in the Library Smart Search box, limiting your search to “Library catalog”.

Michigan Cookbooks: 150 Years of Mostly Good Meals

Published in Conjunction with an Exhibit in the Clarke Historical Library Celebrating the Maureen Hathaway Michigan Culinary Archive

August 22, 2006 - December 21, 2006

Clarke Historical Library Central Michigan University Mt. Pleasant, Michigan 2006

The Science and Technology of Cooking and Cookbooks

Cookbooks, as we understand them today, were invented in the nineteenth century. Although the first cookbook written by an American was published in 1796, the volume would not be useful, or even understandable, to a cook today. Basic technology that is taken for granted by today's cooks, things as elementary as a cooking stove, for example, had not yet been invented. Similarly, there was no reliable method for keeping food cold. The earliest cookbooks in America generally described cooking in a single pot suspended over an open fire in a hearth.[1]

The beginnings of wide-scale change, and what one might call the modern cookbook, first stirred in the 1850s. As early as the 1830s, some far-seeing foundry worker modified a metal stove used to heat rooms by placing a metal box equipped with a door that opened into the room inside the stove. This modification allowed the stove to be used as a crude baking or warming oven. This inventor, or someone of like mind, eventually realized that if holes were cut in the top of the stove enough heat would escape to boil water in a pot, while the stove generated sufficient heat to allow a cook to still use the oven. When this stove design was coupled with a means to control the amount of heat generated by the fire, through a series of grates and dampers that could control the intake of oxygen and thus the rate at which the fire burned, the modern cooking stove was born.[2]

Traditionalists had a lukewarm response to the new invention. Albert Bolles, an early historian of the stove industry, wrote, "The open fire was the true centre (sic) of home-life, and it seemed perfectly impossible to everybody to bring up a family around a stove."[3] Traditionalists were overwhelmed, however, by Americans who bought the new device for two very practical reasons. First, because the stove's dampers could control the size of the fire, wood consumption declined by 50 percent to 90 percent compared to an open hearth, according to stove manufacturers. Second, a stove could be installed by unskilled workers, but hearth construction usually required the assistance of a skilled mason. In a frontier society where skilled labor was often hard to find, this was an important advantage. As they were generally made of cast iron, stoves were not cheap, but they were affordable. In an era when a common laborer's income was about a dollar a day, a typical stove cost anywhere from five to twenty-five dollars. By 1860 cooking stoves accounted for one-third of all the cast-iron products made in the United States.[4]

When coal replaced wood as the primary heating source in homes, it also proved to be a more efficient fuel for stoves. As Edward Everett Hale recalled his mother saying, when he spoke of the beautiful atmosphere and effect of an open-hearth fire in a room, "You may take the poetry of an open wood fire of the present day, but to me in those early days it was only dismal prose, and I am grateful to have lived in the time of anthracite coal."[5]

Nineteenth-century stoves, however, lacked one feature essential to modern stoves, and modern cookbooks, a simple way to control temperatures. The experienced nineteenth-century cook regulated the size of the fire and (when cooking on top of the stove) the distance of the pot or pan from the fire. This practice depended almost entirely on a cook's skill, however, as it was more art than science.

Temperature control, and cookbook recipes based on exact temperatures, became possible at the beginning of the twentieth century when stoves fueled by either gas or electricity were introduced. In 1915 the American Stove Company marketed the first effective oven thermostat for a gas stove. Electric-stove manufacturers were not far behind, introducing thermostats in the 1920s. By World War II, the convenience of gas or electrically heated stoves had led consumers to largely abandon cast-iron stoves, and this meant that oven-temperature controls were now part of most American kitchens.[6]

If the nineteenth century created a means of heating food that is somewhat familiar to today's cooks, it still lacked an essential element of modern cooking and recipes: a practical mechanical means to keep food cold in the home. Food preservation was

a problem in the warm months. By the late nineteenth century, manufactured iceboxes and refrigerators were widely available, though many ill-designed units wasted ice and bred bacteria. As demand outstripped the supply of ice harvested from lakes

and rivers and the new germ theory of disease led customers to fear pollution, commercially manufactured ice came to dominate the market. Between 1880 and 1914, ice consumption increased fivefold in the cities of Chicago, Philadelphia, and Baltimore.

Although it is uncertain whether more than half of all urban families patronized the iceman as late as 1919, most families prosperous enough to buy cookbooks had doubtless acquired refrigerators some time earlier. By the early 1900s, then, most cookbook

users could preserve food and cool it in the refrigerator. But home freezing except in ice-consuming ice-cream makers was not yet feasible.[7]

If the nineteenth century created a means of heating food that is somewhat familiar to today's cooks, it still lacked an essential element of modern cooking and recipes: a practical mechanical means to keep food cold in the home. Food preservation was

a problem in the warm months. By the late nineteenth century, manufactured iceboxes and refrigerators were widely available, though many ill-designed units wasted ice and bred bacteria. As demand outstripped the supply of ice harvested from lakes

and rivers and the new germ theory of disease led customers to fear pollution, commercially manufactured ice came to dominate the market. Between 1880 and 1914, ice consumption increased fivefold in the cities of Chicago, Philadelphia, and Baltimore.

Although it is uncertain whether more than half of all urban families patronized the iceman as late as 1919, most families prosperous enough to buy cookbooks had doubtless acquired refrigerators some time earlier. By the early 1900s, then, most cookbook

users could preserve food and cool it in the refrigerator. But home freezing except in ice-consuming ice-cream makers was not yet feasible.[7]

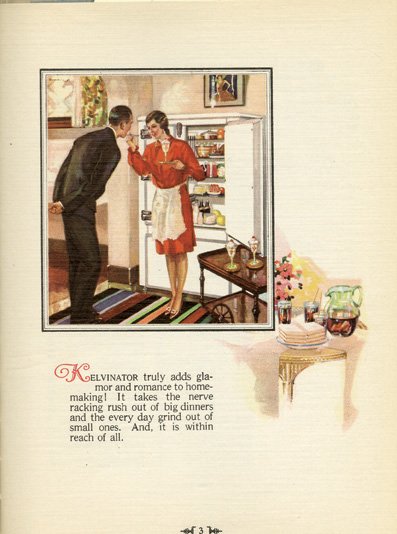

No one person or company solved all of the problems involved in creating the home refrigerator. It took a number of inventions, including the development of an electric compressor small enough for home use in 1914, the appearance of a satisfactory automatic-temperature-control

device in 1917, and the development of the nontoxic, nonexplosive coolant Freon in 1930 to bring home refrigerators into mass production. In 1927 General Electric offered for sale the first machine that looked and worked like the refrigerators we

use today (although it used toxic sulfur dioxide as its coolant). Early electric refrigerators were not particularly dependable. In 1923 electric-utility companies estimated the average machine required a service call once every three months. Despite

this drawback, Americans wanted refrigerators, and by 1941 approximately 45 percent of American households had one.[8]

The variety of foods to put in these refrigerators had been growing since the late nineteenth century. As the national rail network expanded, fruit and vegetables from the South and California appeared in stores, substantially lengthening the season for many foods. Refrigerated rail cars and commercial cold storage were standard by the early twentieth century, enabling city retailers to stock basic items year-round. (Meat, fish, and butter were frozen hard for storage, eggs and produce sharply chilled.) Alternatively, housewives could use canned goods. These were expensive novelties in the 1880s and 1890s, but by 1910 processors such as Heinz produced three billion cans a year. Although that still amounted to only a few dozen cans per person per year, by the 1920s canned foods were absolutely commonplace.[9]

Very quickly electric refrigerators also began to include "freezer units." Food brought to the freezing point slowly bursts its cells, resulting in poor taste when the food is thawed. But food that is frozen quickly allows the cells to remain intact. Frozen food was first introduced to the American public in 1928, and by 1934 thirty-nine million pounds of frozen food was sold in this county. In 1944, only ten years later, the public consumed six hundred million pounds of frozen food.[10]

1 Mary Anna DuSablon, America's Collectible Cookbooks: The History, the Politics, the Recipes (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1994), 1-3; Ruth Schwartz Cowan, More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (New York: Basic Books, 1983), 53-54.

2 Cowan, More Work for Mother, 53-55.

3 Albert S. Bolles, Industrial History of the United States (Norwich, Conn.: H. Bill Publishing Co., 1879), 276; quoted in Cowan, More Work for Mother, 56.

4 Cowan, More Work for Mother, 56-61.

5 Edward Everett Hale, A New England Boyhood and other Bits of Autobiography (Boston: Little, Brown, 1900), 58; quoted in Cowan, More Work for Mother, 58.

6 Cowan, More Work for Mother, 90-97. The first electric stove was demonstrated at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago. Janice B. Longone and Daniel T. Longone, American Cookbooks and Wine Books, 1797-1950 (Ann Arbor: Clements Library, 1984), 10.

7 Oscar Edward Anderson, Refrigeration in America: A History of a New Technology and Its Impact (Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat, 1972), 44-45, 113-15.

8 Cowan, More Work for Mother, 132-34. For a history of the household refrigerator, see Sigfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1948), 599-604.

9 Harvey A. Levenstein, Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 31, 36-37; F. G. Urner, "Food Conservation by Cold Storage," in Fourth National Conservation Congress, Addresses and Proceedings (Indianapolis: The congress, 1912), 328-34.

10 Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command, 599-604.

Commercial Cookbooks

Michigan's cookbooks largely conformed to national patterns. Published cookbooks fell into three broad categories: commercial ventures, corporate publications, and fundraising (charitable) volumes. Books from commercial publishers were the first to appear

and remain quite common. Corporate publications were usually designed to accomplish one of three goals: increase the sales of specific products, encourage the use of a particular appliance, or support the use of gas or electricity by promoting "modern"

cooking using gas or electric appliances. Corporate cookbooks were often viewed as a form of advertising, and they were usually distributed at minimal or no cost to consumers. Fundraising cookbooks were locally produced volumes that first appeared

during the Civil War. These cookbooks were sold, but the money received from sales almost always went to support charitable causes.

Michigan's cookbooks largely conformed to national patterns. Published cookbooks fell into three broad categories: commercial ventures, corporate publications, and fundraising (charitable) volumes. Books from commercial publishers were the first to appear

and remain quite common. Corporate publications were usually designed to accomplish one of three goals: increase the sales of specific products, encourage the use of a particular appliance, or support the use of gas or electricity by promoting "modern"

cooking using gas or electric appliances. Corporate cookbooks were often viewed as a form of advertising, and they were usually distributed at minimal or no cost to consumers. Fundraising cookbooks were locally produced volumes that first appeared

during the Civil War. These cookbooks were sold, but the money received from sales almost always went to support charitable causes.

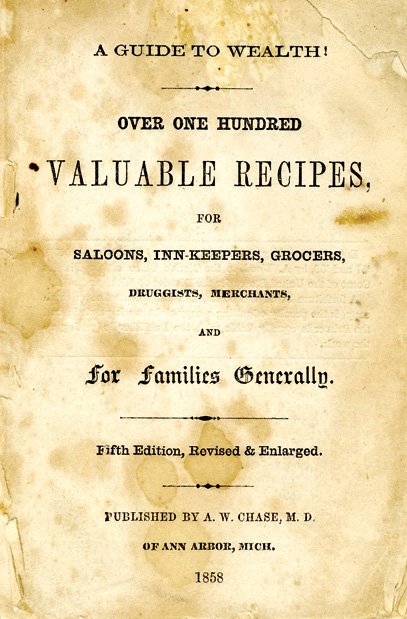

The first commercially successful cookbook published in Michigan was printed in 1858 in Ann Arbor. [11] Alvin Wood Chase's, A Guide to Wealth! Over One Hundred Valuable Recipes for Saloons, Inn-Keepers, Grocers, Druggists, Merchants and for Families Generally, was clearly aimed at a very broad audience. Chase was born in New York State. For many years, however, he lived near Toledo, Ohio, where he was a peddler who, as a sideline, collected and sold folk remedies and recipes. In 1856 Chase moved to Ann Arbor to seek a medical degree at the University of Michigan. Although he never received a degree from the university, while he was a student in Ann Arbor Chase supported himself and his family by selling remedies and recipes. The town's druggist, Christian Eberback, took an interest in Chase, and in 1856, with Eberback's help, Chase published a small pamphlet that included seventeen medicinal formulas.

This pamphlet launched Chase into a successful and lucrative career in printing. In 1858 he published his first book. In 1860 a new volume appeared, containing more than six hundred recipes. The 1863 edition had more than eight hundred recipes. By 1864

Chase's cookbook had become so successful that he constructed the largest steam-powered printing plant in Michigan, primarily to issue ever newer and improved editions of what had become a multipurpose, how-to-guide, as well as a large selection of

recipes.[12]

This pamphlet launched Chase into a successful and lucrative career in printing. In 1858 he published his first book. In 1860 a new volume appeared, containing more than six hundred recipes. The 1863 edition had more than eight hundred recipes. By 1864

Chase's cookbook had become so successful that he constructed the largest steam-powered printing plant in Michigan, primarily to issue ever newer and improved editions of what had become a multipurpose, how-to-guide, as well as a large selection of

recipes.[12] Despite the fact that most cookbooks were published elsewhere, Michigan did have a link to what is arguably the most influential commercial cookbook of the twentieth century, The Joy of Cooking. This work was one of America's most successful

cookbooks. Privately published in 1931, it was issued nationally in 1936 by Bobbs-Merrill and became a huge, enduring success. The book's author, Irma Rombauer, hit upon a formula similar to Della Lutes's: she combined recipes with a chatty style

that many readers found irresistible. Unlike Lutes, however, Rombauer wrote a recipe book with occasional stories and comments, not a storybook with occasional recipes.

Despite the fact that most cookbooks were published elsewhere, Michigan did have a link to what is arguably the most influential commercial cookbook of the twentieth century, The Joy of Cooking. This work was one of America's most successful

cookbooks. Privately published in 1931, it was issued nationally in 1936 by Bobbs-Merrill and became a huge, enduring success. The book's author, Irma Rombauer, hit upon a formula similar to Della Lutes's: she combined recipes with a chatty style

that many readers found irresistible. Unlike Lutes, however, Rombauer wrote a recipe book with occasional stories and comments, not a storybook with occasional recipes.

Fundraising Cookbooks

Fundraising cookbooks are so common today that it is hard to remember a time when they did not exist. However, America's first fundraising "receipt books" were sold during the Civil War to raise money to care for injured soldiers as well as for the widows

and children left behind by those who died. The first receipt book is believed to have been printed in New York City in 1861. After the war was over, the women who had formed the wartime "Ladies Aid Societies" began to sell cookbooks to raise money

for local charities, benefiting countless churches, hospitals, schools, and other institutions across the nation.[1]

When considered solely on their culinary merits, the recipes found in these books are not without their critics. As M. F. K. Fisher, born in Albion, Michigan, in 1908 and a noted food writer of the 1940s and 1950s, archly observed:

A point to be wary about in the usually dependable recipes given in most such collections is the seasoning; it is, to put it mildly, a challenge to your inventive palate, since it either says, "Salt, pepper," or just "Salt." Apparently any other condiments were considered foreign and perhaps even sacrilegious (sic) by members of the Saint James' Sewing Circle in 1902. Otherwise, recipes in such books are dependable, if you like salty things. [2]

Fisher might have had a kinder opinion of these volumes if she had examined some Michigan cookbooks, which discovered seasonings such as thyme in the 1870s (see the recipe for potted pigeons below).

Fisher might have had a kinder opinion of these volumes if she had examined some Michigan cookbooks, which discovered seasonings such as thyme in the 1870s (see the recipe for potted pigeons below).

The majority of fundraising cookbooks eschewed extraneous words. Perhaps to avoid offense or perhaps because the compiler saw the job as publishing the recipes and nothing more, most fundraising cookbooks adopted a policy of "the recipes and just the recipes." Sometimes, however, fundraising cookbooks included various types of commentary. Poetry of varying quality was not uncommon. The following verse preceded the section on "Soups" in the cookbook the Muskegon Woman's Club published in 1912:

One morning in the garden bed,

The onion, carrot, cabbage said,

Unto the parsley group -

"Oh when shall we all meet again,

In thunder, lightning, hail or rain?"

Alas! They cried in tones of pain,

"In the Soup."[3]

Some advice given in 1945 about how much sweetener is necessary in a cherry pie produced this tart observation: "You may need more sugar. A cherry can be as sour as a deacon with a bunion."[4]

Overall these volumes rarely demonstrate literary aspirations. Even the titles are straightforward. For every clever title, such as Our Owen Cuisine, complied by the women of St. Owen in Birmingham, or You Be the Judge by the members of the Ingham County Bar Auxiliary, there are dozens of "Treasured Recipes," "Tested Recipes," or "Favorite Recipes."[5]

Illustrations are not typically found in fundraising cookbooks, either. Normally the only one is found on the book's cover, and even these are modest efforts at best. In church cookbooks, a picture of the church sometimes appears either on the cover or on the first page of the volume. A very modest trend toward including more elaborate illustrative material appears at the end of the twentieth century in some of these volumes.

The first known charitable cookbook published in Michigan appeared in 1871. The Grand Rapids Receipt Book was compiled by the ladies of the Congregational Church.[6] With this publication Michigan became the sixth state to publish a charitable cookbook.[7] A few years later, The Home Messenger Book of Tested Receipts was sold to support

the work of the Detroit Home of the Friendless.[8] The Home Messenger, which endorsed temperance, recommended substituting "one-half ounce of blade mace, steeped in one teacup of lemon juice" for demon rum and other forms

of alcohol.[9]

By the late 1880s and 1890s, cookbooks benefiting churches or church-supported charities had become relatively common in Michigan. In 1887 the Ladies Aid Society of the [Ann Arbor] Methodist Episcopal Church brought forth The Jubilee Cook Book. The Grand Rapids Cook Book,

which was compiled by the "Ladies of Grand Rapids" on behalf of the Congregational Church, was published in that city in 1888. What the Baptist Brethren Eat and How the Sisters Serve It, was compiled by the ladies of the First Baptist

Church (Port Huron) in 1889. In 1893 The Charlotte Cook Book: A Selection of Tested Recipes was prepared by the ladies of the First Congregational Church and published locally. In 1895 the ladies of the Pilgrim Congregational Church

[Lansing] published The Pilgrim Cook Book. Closing out the century, the Ladies Aid Society of the [Ann Arbor] Congregational Church published The Ann Arbor Cookbook in 1899.[10]

Church organizations were among the earliest, and remain some of the most prolific, publishers of Michigan cookbooks. Other charitable organizations, however, soon recognized the value of cookbooks in fundraising. Among the first Michigan examples of

cookbooks in support of nonreligious organizations are The Dinner Bell, 1889, the O.E.S Cook Book, published sometime between 1895 and 1910, the Fremont Grange Cook Book, 1904, and the Sebewaing Cook Book: A Selection of Tried and True Recipes,

which was compiled by the Sebewaing ladies for the benefit of the Sebewaing General Hospital and published in 1912.[11]

Fundraising cookbooks were printed in great numbers throughout the twentieth century and continue to be a fundraising tool of the twenty-first century. The fact that cookbooks have become regular features in some institutions' fundraising activities illustrates

the continued vitality of this tool for soliciting funds. Institutions repeatedly go "back to the well," issuing new books as time passes. For example, the Detroit Institute of Arts has printed at least two fundraising cookbooks during the past twenty

years. An even more striking example of this phenomenon is the twenty-one volumes published under the title Le Gala de Cuisine, spanning the years 1978-1999, that have accompanied an annual dinner benefiting the Cranbrook Schools located

in Bloomfield Hills.[12]

Le Gala de Cuisine is also striking in that it contradicts a trend that began in the 1930s: specialty printers that exist solely to issue fundraising cookbooks. The appeal of such printers is obvious. Organizations can avoid the problems

involved in the actual production of such volumes. Although this choice clearly benefits many organizations, using such companies could lead to unexpected results. For example, Fundcraft Publishers of Pleasanton, Kansas, a popular printer for fundraising

cookbooks, was fond of the title, Butter 'n Love Recipes. As a result, between 1977 and 1984 no fewer than eleven Michigan groups published a cookbook under that title, including the Baldwin Lioness Club (1984); the Happy Clovers 4-Club

of Niles (1984); St. Paul United Methodist Church of Cheboygan (1984); St. Paul Lutheran Church of Temperance (1982); Big Beaver United Methodist Women of Troy (1981); Reed City United Methodist Women (1981); the Romeo Elkettes (1981); the First Congregational

Church, Winthrop Circle, of St. Clair (1980); the Li Tah Ni Chapter of the American Business Women's Association of Flint (1977); Eagles Auxiliary no. 3655 of Beaverton (1977); and the Women of the Moose, chapter 1135 of Belleville (1977).[13]

Le Gala de Cuisine is also striking in that it contradicts a trend that began in the 1930s: specialty printers that exist solely to issue fundraising cookbooks. The appeal of such printers is obvious. Organizations can avoid the problems

involved in the actual production of such volumes. Although this choice clearly benefits many organizations, using such companies could lead to unexpected results. For example, Fundcraft Publishers of Pleasanton, Kansas, a popular printer for fundraising

cookbooks, was fond of the title, Butter 'n Love Recipes. As a result, between 1977 and 1984 no fewer than eleven Michigan groups published a cookbook under that title, including the Baldwin Lioness Club (1984); the Happy Clovers 4-Club

of Niles (1984); St. Paul United Methodist Church of Cheboygan (1984); St. Paul Lutheran Church of Temperance (1982); Big Beaver United Methodist Women of Troy (1981); Reed City United Methodist Women (1981); the Romeo Elkettes (1981); the First Congregational

Church, Winthrop Circle, of St. Clair (1980); the Li Tah Ni Chapter of the American Business Women's Association of Flint (1977); Eagles Auxiliary no. 3655 of Beaverton (1977); and the Women of the Moose, chapter 1135 of Belleville (1977).[13]

Despite all of their limitations , fundraising cookbooks are quite valuable to researchers. As Mary Anna DuSablon notes, charitable cookbooks are not usually for beginners because they assume a certain basic knowledge of cooking, but they are also usually not "an exhibition in food fantasy." Typically, they avoid the excesses that professional chefs, food magazines, and even corporate publications sometimes adopt in their quest for novelty. Admittedly, DuSablon's advice should be taken with a grain of salt (pepper optional); upscale communities do occasionally produce fundraising cookbooks featuring recipes of considerable complexity that rival the "food fantasies" of professional chefs. Sometimes these volumes are even written by professional chefs. In the end, however, fundraising cookbooks document what the locals were cooking, salt and all, at a specific time and place. And this is what makes them valuable to historians. [14]

Corporate Publications

Food

manufacturers, which canned, processed, refrigerated, and eventually froze all manner of food, quickly discovered that consumers were often unfamiliar with how to use the products they were offered. One way to improve consumer knowledge, and increase

sales, was to develop recipes using the firm's products and distribute those recipes to consumers. Often these recipes were conveniently printed on the box or can in which the product was sold.

Food

manufacturers, which canned, processed, refrigerated, and eventually froze all manner of food, quickly discovered that consumers were often unfamiliar with how to use the products they were offered. One way to improve consumer knowledge, and increase

sales, was to develop recipes using the firm's products and distribute those recipes to consumers. Often these recipes were conveniently printed on the box or can in which the product was sold.  Promotional

cookbooks printed by food and kitchen-equipment companies first appeared in America after the Civil War.[18]Michigan companies, particularly cereal manufacturers located in Battle Creek, played an important role in printing and distributing

corporately produced recipes and cookbooks. C. W. Post and W. K. Kellogg, both of whom made fortunes in breakfast cereals and spawned large numbers of local imitators, pointed out the importance of advertising to their success. "All I have I owe to

advertising," Post was quoted as saying.[19] W. K. Kellogg had the same faith in advertising. In the early days of the production of corn flakes, he invested one-third of his available funds in a single ad published in the

Ladies Home Journal.[20] Both men happily printed recipes that always included at least one of their many products, and their successors in a variety of industries enthusiastically continued this tradition.

Promotional

cookbooks printed by food and kitchen-equipment companies first appeared in America after the Civil War.[18]Michigan companies, particularly cereal manufacturers located in Battle Creek, played an important role in printing and distributing

corporately produced recipes and cookbooks. C. W. Post and W. K. Kellogg, both of whom made fortunes in breakfast cereals and spawned large numbers of local imitators, pointed out the importance of advertising to their success. "All I have I owe to

advertising," Post was quoted as saying.[19] W. K. Kellogg had the same faith in advertising. In the early days of the production of corn flakes, he invested one-third of his available funds in a single ad published in the

Ladies Home Journal.[20] Both men happily printed recipes that always included at least one of their many products, and their successors in a variety of industries enthusiastically continued this tradition. Ethnic and Regional Cooking

The "receipt books" of the Civil War era and their fundraising successors not only created new purposes for cookbooks but also documented what cooks in the place of publication thought good enough to share. These volumes published the recipes of local cooks, and they were intended primarily for members of the local community. Although the recipes in these books were not exclusively regional, fundraising cookbooks focused on local favorites. Because of this local focus, fundraising cookbooks became, quite unintentionally, the first American "regional" cookbooks,[3] and also document how recipes moved from region to region.

A second group of cookbooks, ethnic cookbooks, sought also to go beyond the advice of commercially published books from "back East." Throughout much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries America was the chosen destination of millions of immigrants.

These immigrants, however, often longed for a taste of the homeland, which they did not find in a New England pot roast, however seasoned, printed in a cookbook benefiting the local Congregational Church.

A second group of cookbooks, ethnic cookbooks, sought also to go beyond the advice of commercially published books from "back East." Throughout much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries America was the chosen destination of millions of immigrants.

These immigrants, however, often longed for a taste of the homeland, which they did not find in a New England pot roast, however seasoned, printed in a cookbook benefiting the local Congregational Church.

Ethnic cookbooks served two purposes. First, the books, which were sometimes published in the language of the immigrant community, helped immigrants recapture the flavor of the old country but used ingredients found in their adopted home. American stores usually lacked the ingredients immigrants were accustomed to using, but clever cooks have adopted old recipes to new surroundings for generations, and these new cookbooks helped immigrants to do just that.

Second, ethnic cookbooks included recipes for dishes that mothers, and later grandmothers, served. In so doing, these cookbooks practiced cultural preservation by saving old-world recipes, although these recipes often reflected grandma's Americanized

version of the dish. This combination could raise objections from cultural purists. A small but telling example of this conflict between the New World and the Old World is seen in the rendering of the Polish word for duck blood soup in cookbooks published

almost a half-century apart. In 1948 Treasured Polish Recipes for Americans, published in America, gave the Polish word for the soup as "czarnina." Robert Strybal, a native of Michigan who wrote the syndicated column "Polish Chef,"

spelled the word "czernina" in his 1993 book, Polish Heritage Cookery. Noting the different spellings, Strybal, announced that "the spelling is 'czarnina' in peasant dialect," a distinction that resonates with just a hint of distaste

for cookbooks that could not keep straight "real" ethnic cuisine from the peasant fare immigrants tended to eat.[4]

Second, ethnic cookbooks included recipes for dishes that mothers, and later grandmothers, served. In so doing, these cookbooks practiced cultural preservation by saving old-world recipes, although these recipes often reflected grandma's Americanized

version of the dish. This combination could raise objections from cultural purists. A small but telling example of this conflict between the New World and the Old World is seen in the rendering of the Polish word for duck blood soup in cookbooks published

almost a half-century apart. In 1948 Treasured Polish Recipes for Americans, published in America, gave the Polish word for the soup as "czarnina." Robert Strybal, a native of Michigan who wrote the syndicated column "Polish Chef,"

spelled the word "czernina" in his 1993 book, Polish Heritage Cookery. Noting the different spellings, Strybal, announced that "the spelling is 'czarnina' in peasant dialect," a distinction that resonates with just a hint of distaste

for cookbooks that could not keep straight "real" ethnic cuisine from the peasant fare immigrants tended to eat.[4]

Authenticity, however, is difficult to define in this context. Those bent on capturing true old-world recipes could remove the processed American food products that had crept into grandma's version of the dish and replace them with something more authentic. At the same time, however, the children and grandchildren of immigrants could enjoy an "authentic" recipe from grandma that included those products. Both groups could argue that they were preserving an "ethnic" recipe.

In America ethnic cooking was and remains a two-way street. While immigrants were integrating "American" food products into their traditional recipes, Americans were integrating "foreign" foods into American cuisine. The result was often a unique blending of old and new that, in its most creative mode, gave the United States "foreign" recipes invented in North America. Chop suey and spaghetti with large meatballs did not come in their American form from, respectively, China and Italy, but from cooks in the United States who adapted old-world recipes to new-world tastes. This process continues today as new immigrants and American cooks mix national favorites and American ingredients in a culinary give-and-take.[5]Gender Roles and Cooking

It will surprise no one that in the United States cooking has historically been identified as women's work. The question "Who is going to cook dinner?" however, has slowly developed a more nuanced answer. Although women still cook more frequently than

men do, for a man to cook a meal is clearly no longer an unusual event.

It will surprise no one that in the United States cooking has historically been identified as women's work. The question "Who is going to cook dinner?" however, has slowly developed a more nuanced answer. Although women still cook more frequently than

men do, for a man to cook a meal is clearly no longer an unusual event.

Identifying the root cause of any social change is always difficult. Several things, however, likely led men to develop at least a passing acquaintance with cooking. One of these factors occurred in suburban backyards in the 1950s. The backyard cookout became fashionable during that decade, and cooking in the yard was a man's job.

We have . . . definite opinions about charcoal

cookery. We believe that it is primarily a man's job and that a woman,

if she's smart, will keep it that way. Men love it, for it gives them a

chance to prove that they are, indeed, fine cooks. [10]

Helen Evans Brown and James Beard, who wrote the above paragraph, were not alone in their opinion. Victor Bergeron (founder of the then popular Trader Vic's chain of restaurants) reassured men in 1952: "You can take my word for it that a yen to cook is in the same rugged tradition as jousting or going on a crusade to fight the Saracens."[11] A few years later, Gertrude Booth, went even farther:

We

contend that men are better cooks than women, and it is with a great

deal of pride that we give you these recipes from men of all parts of

the country. Cooking, with a man, is an urge from the heart - he has a

great natural talent and he has been at it longer than woman. [12]

Regardless of the natural talent men had or did not have for cooking, the trend in the 1950s toward men cooking was a slippery slope. If men as a group were fine cooks, as Brown and Beard asserted, or even better than women, as Booth would have it, and a specific man successfully proved the point by cooking an edible slab of meat over a grill, surely he could with equal success put a TV dinner in the oven, a boil-in-bag in a pot of water, or an entrèe into a microwave. And having mastered the use of cooking devices not employing charcoal, it was inevitable that the next step would soon occur to men: actually reading a cookbook.

Men's theoretically increasing responsibility for meal preparation also reflected the demographic shift in the workplace as an ever-increasing number of women worked outside of the home. This meant that in many families both parents worked, and when this

was the case, something had to give. What gave first was largely the amount of time that could be devoted to cooking.

Men's theoretically increasing responsibility for meal preparation also reflected the demographic shift in the workplace as an ever-increasing number of women worked outside of the home. This meant that in many families both parents worked, and when this

was the case, something had to give. What gave first was largely the amount of time that could be devoted to cooking.

Cookbooks were an early indicator of this change. Maude Stewart Beagle wrote in the introduction to her book, Can Opener Recipes for the Career Wife: "If you are a career wife who does her own cooking for a husband who likes meals with a Duncan Hines recommendation then draw up a chair, sister, and take out the old can opener. You have found one just like yourself. After many years of careering and cooking quite successfully, at least I'm still living with the same husband I started out with, I have decided to write this book." Beagle clearly recognized the problem of completing household chores in a dual-income family.[13] Her can opener would eventually be supplemented by a microwave, but the intent was clearly the same: cooking a meal with as little effort and time as possible.

Cooking faster, however, was not the complete answer. Very soon men were asked to do more housework, including cooking. Although statistics indicate that women living in dual-income households still do a larger share of the housework than men, the amount of work done by men, including cooking, appears to have increased over time.[14]

Conclusion

Cookbooks prompt us to ask questions about gender, ethnicity, nutrition, class, and taste. The person who opens a cookbook may do so simply because he or she is looking for a new way to prepare chicken. A researcher, however, can open the same cookbook and learn a great deal about our culture and ourselves. Cookbooks are clearly not just for cooking.

1 Information regarding Rice Krispies Treats was found on Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rice_Krispies. Site visited on July 3, 2006. Despite the recipe's age, the treat (and the cereal) remains popular. The Kellogg Company currently makes the recipe available in three forms, (regular, microwave, and large quantity) on its website at http://www.kelloggs.com/. Site consulted July 5, 2006. See also Camp Fire Cookery for Camp Fire Girls (Battle Creek: Kellogg Co. Home Economics Department, [1955]); Trail Cookery for Girl Scouts (Battle Creek: Kellogg Co. Home Economics Department, [1955]); and A Manual of Cooking for Boy Scouts (Battle Creek: Kellogg Co. Home Economics Department, [1935]).

2 Mother Hubbard's Modern Cupboard (Battle Creek: Little-Preston, 1903), 89. For more information regarding Tryabita, see Sylvia Lovegren, Fashionable Food: Seven Decades of Food Fads (1995; repr., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 260; Carson, Cornflake Crusade, 183; and Massie, "Romance of Old Cookbooks," 49.

3 Eleanor Brown and Bob Brown, Culinary Americana: Cookbooks Published in the Cities and Towns of the United States of America during the Years from 1860 through 1960 (New York: Roving Eye Press, 1961), vii-viii.

4 Robert and Maria Strybel, Polish Heritage Cookery (New York: Hippocrene Books, 1993), 195; Treasured Polish Recipes for Americans (Minneapolis: Polanie Publishing Co., 1948), 22-23.

5 Lovegren, Fashionable Food, 89. Lovegren notes that while Americans had heard of spaghetti, as late as 1922 the Good Housekeeping Institute recommended that it be boiled for a minimum of thirty minutes, tossed with butter, and "served hot as a vegetable." Spaghetti with some variant of tomato sauce appears in cookbooks of the 1920s with such unflattering and racist titles as "Wop Spaghetti," or "Dago's Delight." Ibid., 35.

10 Helen Evans Brown and James Beard, The Complete Book of Outdoor Cookery (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1955); quoted in Lovegren, Fashionable Food, 168-69.

11 Lovegren, Fashionable Food, 170.

12 Gertrude Booth, comp., Kings in the Kitchen: Favorite Recipes of Famous Men (New York: Barnes, 1961).

13 Maude Stewart Beagle, Can Opener Recipes for the Career Wife (Flint: The author, 1951), 9-10.

14 For the year 1967, the United States Department of Labor, Bureau

of Labor Statistics reports that among married individuals with families, 35.6 percent of the families were supported economically solely by the husband, 1.7 percent were supported solely by the wife, and 43.6 percent were supported by the

employment of both husband and wife. In 2003 those number had changed respectively to 18.1 percent, 5.2 percent, and 57.5 percent. Statistics viewed July 3, 2006, at http://www.bls.gov/cps/wlf-table23-2005.pdf.

Whether men are doing more housework as a result of this shift is a contested question. A study by the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research released in 2002 indicates that the number of hours men devoted to housework increased

from twelve in 1965 to sixteen in 1999. In 1999 women performed twenty-seven hours of housework per week. Study cited on the following website z http://www.applesforhealth.com/

MensHealth/mdohoh3.html. Site visited on July 3,

2006. Also see Andrew Singleton and Jane Maree Maher, "'' The New Man' Is in the House: Young Men, Social Change, and Housework," Journal of Men's Studies 12 (Spring 2004): 227-240 . Singleton and Maher suggest that although

the rhetoric regarding the distribution of housework between spouses has changed over the past fifty years, the reality of who does the work may not have changed significantly.