The Historical Context Preceding Treaty Negotiation in the 1820s

The Historical Context Preceding Treaty Negotiation in the 1820s

An essay by Joshua D. Cochran and Frank Boles

In the early years of the nineteenth century Native Americans leaders in the Great Lakes region were well schooled personally and through knowledge shared with them by their elders regarding ways to exploit European rivalries within North America . This was not abstract knowledge. Understanding the nature of European conflict was critical information used by Indian leaders in their negotiations with Europeans. They also understood that Indian military prowess played an important role in European considerations. Indians had historically been an effective fighting force. They could forward their own interests by force of arms; use this force on behalf of Europeans as allies and in exchange for concessions, or promise peace, for the right price.

Skillful exploitation of European differences, coupled with the significant military forces Indian nations could bring to bear for or against European interests, created opportunities through which to win diplomatic victories for Indian nations. Indian leaders in theGreat Lakes region had used their military strength and ability to exploit European differences to obtain favorable outcomes in negotiations for at least a half-century.

Indian leaders first discovered the power of this strategy when they spoke with the rival colonial empires of France and England . Threats to the Indians created by large-scale British settlements could be played against French economic interests far more concerned with the fur trade and willing to arm and supply Indian allies who would oppose the British. Similarly, disadvantageous French economic decisions could be countered by recourse to British colonial officials seeking to limit the possibility of Indian warfare against the ever-expanding British colonial population.

Tension between England and France in other parts of the world sometimes created opportunities in which either country was willing to reward the NativeAmerican population if they would either pledge peace or offer to take up arms. Indian leaders became skilled at playing one European power against the other, to maximize tribal interests.

The ability of Indian leaders to manipulate European rivalries for their own benefit was endangered in 1760s when French military forces in North America were crushed by the British. With the exception of a few small islands off the Canadian shoreline, all of New France was formally and permanently ceded to Britain . The victorious British treated Native Americans as if they, like the French, had been vanquished. In the war'simmediate aftermath various forms of support were lessened or abolished. Key British officials, focused on saving money after the expenses of war, failed to understand that their policy angered Native American leaders who had sided with them and who believed they deserved a share of the victor's spoils. The policy also angered the leaders of France 's Native American allies who were quite clear in their own minds that it had been the French, not they, who had surrendered.

In 1763 Britain 's shortsighted policy led to Pontiac 's Revolt; a pan-Indian movement that developed a coordinated military strategy with the objective of driving the British from all settlements west of the Alleghany Mountains . The revolt failed in its military objective but the narrowness of Britain 's victory made clear the military prowess of Native Americans. This realization made the conflict important politically. British officials quickly changed policies in an effort to win Native American goodwill.

The realization of the continued military significance of Native American tribes came at a time when Britain was coming into increasing conflict with its own colonies in North America. Within a generation of the collapse of New France , Native Americans would again find their interests advanced by balancing two great powers against one another: the British in Canada against the newly established United States of America. America's insatiable westward expansion had grave implications for the Indian nations and potentially disturbing political ramifications for the British. Each had good reason to support the other in checking the American's advance.

The era of British-American conflict on the North American continent lasted approximately fifty years. The War of 1812 was the final opportunity for Native American nations in the Northwest Territory to ally themselves with a European power, Britain, in an effort to limit the expansionist goals of the Euro-Americans residing in the United States. The War of 1812 would also represent the last time the tribes of the Great Lakes region could muster sufficient military strength to challenge directly the United States military. We know this today, but nineteenth-century leaders, both Native American and Euro-American, who were responsible for negotiating treaties with one another could not be so sure about the course of future events.

At the close of the War of 1812 the United States, in particular, had to weigh carefully the course of future Native American relations. Provisions of the American constitution in 1787 had provided for the negotiation of treaties with Native Americans. The American military's history in the Northwest Territory prior to the War of 1812 strongly suggested that negotiations, rather than an initial recourse to military force, would be a wise policy for the leaders of the new Republic to follow. [1]

In the 1780s Native American leaders in the Northwest Territory developed a pan-Indian alliance similar to that led by Pontiac in the 1760s. This alliance created a military force very much the equal of that available to the United States on the frontier. A series of battles and lesser skirmishes occurred on the western frontier. In these battles the pan-Indian alliance proved itself quite capable of defeating the new Republic's military.

In the fall of 1790, militia units led by General Josiah Harmar suffered a humiliating defeat in an attack against members of the Miami tribe in present-day Ohio. Harmar encountered not only The Miami led by the chief Little Turtle and aided by his Shawnee counterpart BlueJacket, but also many warriors from the Potawatomi, Ottawa, Chippewa, and Delaware tribes. [2]

A year later a second military force, under the command of Arthur St. Clair, experienced the same outcome. St. Clair and his 1,400 militia troops were attacked by a united band of Chippewa, Potawatomi, Ottawa, Miami, Delaware, Wyandot, Shawnee, Mingo, and Cherokee Indians. The surprise attack cost St. Clair half of his command. The defeat also led the federal government to reconsider its use of local militias as the primary means of combating Native Americans on the frontier. If the Native Americans' military power was to be matched, Congress would need to finance a professional army to do it. [3]

The use of professional soldiers gave the American government the means to match the Native Americans. In August 1794 at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, Anthony Wayne and his 3,000 soldiers defeated the confederated tribes who were attempting an ambush. Because the number of casualties was approximately equal, some scholars contend that labeling the battle a “victory” for Wayne is a misnomer. However, the battle was a victory for the Americans in that it severely damaged the inter-tribal alliances among the Native Americans and led to the first negotiations between the American government and Native American leaders in the region. The result was finalized in the Treaty of Greenville, signed in August 1795.

The treaty in large part reflected the aims of the federal government. It allowed the establishment of military posts in the Northwest and ceded the United States all of present-day Ohio, southern Indiana, and Illinois. However, the military success of the tribes in the early 1790s was not forgotten, either by the tribes or the negotiators from Washington. The treaty allowed some provisions favorable to the Native Americans in order to end the fighting on the frontier. In particular, the document required that payments be made by the federal government of a thousand dollars per year to many of the tribes in the area. [4]

The treaty of Greenville demonstrated serious practical shortcomings in the pan-Indian alliance, but the dream of an alliance remained alive among some Native American leaders. Nor did the Battle of Fallen Timbers put an end to the military power of the Native Americans. Native American leaders remembered both their strength and their traditional negotiating tool of playing one European community against another. By 1811 Tecumseh, a Shawnee leader, along with his brother, The Prophet, had resurrected the Native American alliances of the 1780s and again threatened to counter Euro-American settlement with military force. In November 1811, errors in judgment on the part of The Prophet led to a Native American defeat at the Battle of Tippecanoe. Although the battle went badly for the Native Americans, as at the battle of Fallen Timbers the more serious problem was a fracturing of the pan-Indian alliance.

With the outbreak of war in 1812 between Britain and the United States Tecumseh, who unlike the now-discredited Prophet retained a significant pan-Indian following, allied himself with the British. Tecumseh's Indians played a major role in the British capture of Detroit, an extremely disheartening loss suffered by the Americans in the war's first year. In 1813, however, Tecumseh died in southern Ontario at the Battle of the Thames. There was no Native American leader of sufficient stature to take his place, causing the pan-Indian alliance to further falter. Adding to the Indians' problems, at the war's close the British home government ordered that support for Native Americans be severely curtailed or completely ended. The Native American nations of the Great Lakes found themselves lacking a unifying figure, their military power greatly diminished by significant casualties in several years of the ongoing war, and without significant support from the British in their struggle against the United States.

Treaty Making on the Great Lakes in the 1820s

During the 1820s the situation confronting Native American leaders was disheartening. Britain no longer was willing to support them. Their own resources through which to make war had diminished. Most importantly, the settlers from the United States kept coming in ever larger numbers. Given their situation, many Native American leaders seemed to believe that their only recourse was to negotiate the best possible treaty with the United States government. It was likely, however, that most Native American leaders realized even the best possible treaty with the land-hungry Americans would not be very much.

The United States, too, had seen a great deal of war, and Washington also wished to find a negotiated way to resolve the “Indian problem” in the Great Lakes. As Euro-American westward expansion forced Native tribes and settlers into increasing geographical and cultural contact, the federal government sought comprehensive policies and treaties that aimed at achieving five objectives:

- Gaining allegiance from tribes that previously had sided with Britain

- Gaining title to the land for westward settlement

- Ensuring the safety of those settlers

- Accessing land for the purposes of extracting resources, particularly Michigan copper

- Ensuring total control over the region—legally, politically, and militarily

To accomplish these comprehensive objectives; Washington's negotiators typically sought three components in treaties. The major treaties between the government and the Great Lakes tribes drafted during the 1820s included:

- Well-defined boundaries of land for specific tribes to occupy

- Policies that encouraged tribal members and leaders to become “civilized”

- Frameworks for supplying tribes with goods and resources to survive while tribal members learned “civilized” ways

In truth, the leaders of the new nation in Washington were uncertain what the nation's policy should be toward Native Americans. In the first years of the 1820s, the political majority in Washington argued that the solution to the “Indian problem” was “civilization.” Native Americans were to be shown the benefits of European lifestyle and progressively brought under that culture's norms and expectations.

The first step in civilizing the Native American population was to convince them to live as Euro-Americans' did; in settled communities that had well-defined boundaries. Thus, in this period the treaties that were negotiated and ratified made an effort to assign specific land with well-defined borders to each tribe. Boundaries rarely served Native American interests. For the tribes who already resided in the land, they usually meant less land on which to live and less mobility to follow the game. In many cases, it required abandoning lands that tribes had traditionally occupied and which possessed ceremonial or cultural significance for them.

Once boundaries were established the objective was to persuade Native Americans to abandon their traditional values and lifestyle. More specifically, Washington encouraged Native Americans to replace hunting with farming. Supplementing and supporting this change, Washington believed, was the adoption by Native Americans of Christian values and principles to replace Indigenous beliefs. In theory, at least the political leaders in Washington also realized that Native Americans would need food, trade goods, and other resources such as access to Euro-American educational facilities to help them successfully make this transition.

An alternate view that emerged in Washington asserted that Native Americans had little interest in European ways, preferring to retain their own cultural heritage. Those who despaired of “civilizing” Indians generally came to conclude that the only solution was to send Native Americans away, usually far away, from Euro-American settlements. By the late 1820s a policy of relocation, rather than civilization was gaining ascendancy in Washington. Native American representatives sitting at treaty sessions within the Great Lakes region during the 1820s faced an uncertain federal policy which sometimes sought “civilization” as its goal while at other times simply wanted to remove Native Americans to somewhere in the West.

Regardless of whether the federal government wished to civilize Native Americans or remove them, separating warring tribes was always a critical concern. Thus at Prairie du Chien, a hamlet in present-day Wisconsin, in the summer of 1825, the Bureau of Indian Affairs sent Michigan Territorial Governor Lewis Cass and Army General William Clark to resolve long-standing inter-tribal disputes among the Sioux, Chippewa, Sauk, and Fox, Winnebago, Iowa, and Illinois. The Sioux and the Chippewa stood at the brink of full war. Indian agents expressed concern that the tribal wars threatened white settlements. Indeed, Indian agents feared the hostilities might expand to all tribes in the Mississippi and Great Lakes region. [5]

The negotiations at Prairie du Chien centered on establishing permanent boundaries for tribes in order to end the inter-tribal violence, but they also showed the tendency of Washington's negotiators to insert other, unstated agendas into the negotiation. William Clark told the tribes that had assembled that, “the Great Fathers were displeased with the squabbles of his red children,” and “he did not come here seeking land.” Although this was not a complete falsehood, Clark and Cass, in drawing specific boundaries for each tribe, also created through the treaty at Prairie du Chien “empty spaces” available for Euro-American settlement.

It is likely that Native Americans at the negotiations understood what was happening, but their lack of unity made it difficult to create a collective opposition to this result. The speeches of tribal leaders at several treaty proceedings during the 1820s made obvious the collapse of the pan-Indian alliance masterminded by Tecumseh. In particular, response to the federal government's unending request for land, whether directly stated or indirectly achieved, varied dramatically.

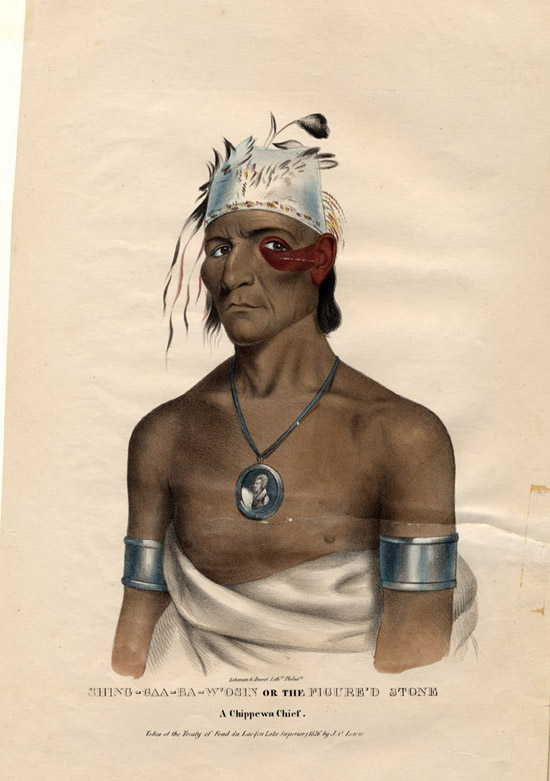

There were those who steadfastly opposed giving land to the Euro-Americans. The Chippewa chief Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin ( Figured Stone) eloquently exemplified this position. At the treaty negotiations at Fond du Lac, Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin, who had repeatedly suggested that he would resist White settlement, rejected efforts on the part of the federal negotiators to change his position. As the conference drew to its close Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin observed one of the federal government's negotiators seated on a tree stump. Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin made his way to the same stump and sat very close to the negotiator, practically pushing him off the tree. When the negotiator moved to another log Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin followed him, eventually pushing the negotiator onto the ground.

Looking at the man lying in front of him, Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin spoke:

There, my Father, that is the way in which you serve your poor red children. The Great Spirit hears me, and I will speak. I came and asked you for a seat on which to rest my limbs; you gave it to me. Not contented with this, I urged you for more until you gave and I again demanded more until you had none left. Many moons ago, our Father crossed the Big water [ Atlantic Ocean ] and begged of his red children a small piece of land on which he might build his wigwam. It was given to him; but not being satisfied, he again asked his red children for more. This was given, and still more until his red children abandoned the homes and hunting grounds of their fathers to make way for the white man. Now when the great chiefs and braves of their nations are at rest, our Father is for sending us further west to where the sun sets and sinks into the Big Lake [Pacific Ocean]. [6]

Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin, however, was not the only voice to be heard among the tribal leaders. He likely represented a minority of those Native Americans who had come to negotiate a treaty. Other Native American leaders were willing to forfeit their lands. Their motives for doing this are often unclear. They were sometimes accused of selling their tribal land in order to curry favor with Washington . At Fond du Lac , one Chippewa leader from the Ontonagon commented,

My Father, you gave me a medal and a flag at the Ontonagon. They say I have sold my country for these things. You, father, know better you told me to sit still and hold down my head, and if I hear bad birds singing, to bend it still lower. My friends held down their heads when I approached. When I turned bad words went out of their mouths against me.[7]

Those who took the position that the land could be given up often sounded weary of conflict and resigned to the inevitable. They may have believed that the old game of playing one European power off against another was ended, as was the possibility of successful military actions against the Euro-Americans. Thus, they could only make the best out of a bad situation.

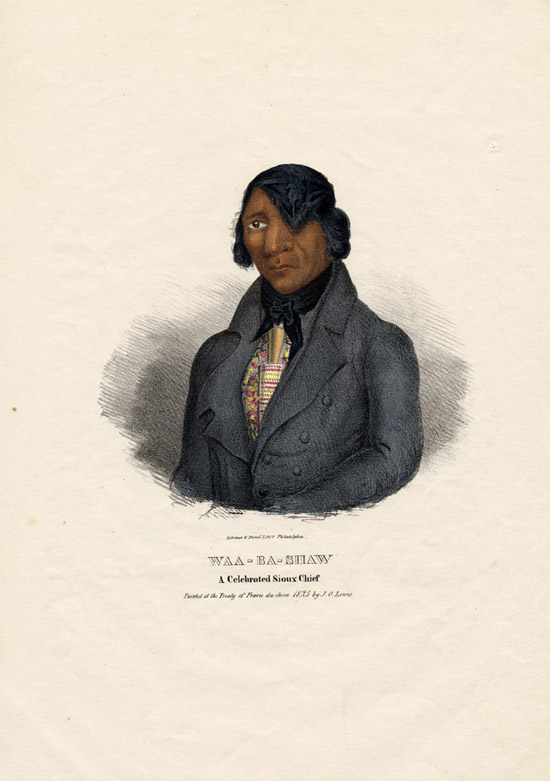

At Prairie du Chien the Sioux Chief, Waa-Ba-Shaw (also spelled as Wahpasha) demonstrated this attitude of weariness and resignation. During the proceedings he commented on the affects of the westward expansion on his tribes and on his own land ownership, stating,

I will relinquish some of my lands for the sake of peace, -- I formerly owned the land on which we now are but I do not claim it now because it belongs to the Whites. [8]

Waa-Ba-Shaw himself was a well-regarded chief among his band of Sioux and a man whose family had wide experience in dealing with Europeans. He was believed to have been born sometime around 1773. Waa-Ba-Shaw's father (also known as Waa-Ba-Shaw) was an important tribal leader. Upon the death of Waa-Ba-Shaw the elder in 1806, his son, Waa-Ba-Shaw, took control of the band and established an encampment near present day Winona , Minnesota . Although in the 1820s many considered Waa-Ba-Shaw a pacifist, during the War of 1812 he aligned himself and his warriors with the British forces and apparently served the king with distinction. At the close of the war, however, Waa-Ba-Shaw believed the British had betrayed him and his people. Waa-Ba-Shaw signaled his deep displeasure with the British by refusing British tokens of respect offered him at Michilimackinac. [9]

In abandoning the British, Waa-Ba-Shaw lost the ability to play European against European. Without the British supplying weapons, he seemingly concluded that making peace with the Americans was his only option. Waa-Ba-Shaw, historians report, enjoyed relatively friendly relations with the American settlers who moved into the frontier. He met with all the explorers and agents sent to the region and even visited Washington in 1824. [10]

Although Waa-Ba-Shaw may have foresworn war as a tool of diplomacy, leaders such as Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin made it clear to officials in Washington that there was still the possibility of Native Americans militarily opposing Euro-American settlement. Nor could Washington rest easy that Britain might not once again use Indians as part of an anti-American policy. These fears wee reflected in two clauses found in the treaty signed at Prairie du Chien. The clauses required that:

- The tribes recognize the authority of the United States to direct the course of Native American relations and treaties

- Statements in which the Native American signers relinquished all ties to any other powers and people in the region

The ghosts of the War of 1812 and the fear that not all of the Great Lakes' Indian leaders had come to believe, as did Waa-Ba-Shaw, that there was no alternative to accepting endless Euro-American settlement are clearly written into these clauses.

Article 12 of the Prairie du Chien treaty was in some ways an admission that, whatever other merits it might have, the treaty had failed in its primary purpose. The article called for a new round of negotiations in the next year to establish clear demarcation between Sioux and Chippewa land.[11] The significance placed on this new round of talks was signaled when Thomas McKenney, head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington , D.C. , traveled from the capitol and joined Michigan 's territorial governor Lewis Cass. Together the men went to Fond du Lac , an outpost near Lake Superior for this new round of talks.

This meeting brought together leaders of the Chippewa tribe, many of whom had been absent from the proceedings at Prairie du Chien a year prior. Once again while the primary goal stated by government officials was to further reduce contact and therefore hostilities between the Chippewa and Sioux tribes, other agendas became evident in the discussions. These agendas reflected the many goals of the federal government's Indian policy.

The commissioners urged that the tribes resolve their disputes by becoming “civilized.” Washington 's representatives argued that tribal conflict stemmed from confrontations over hunting grounds. If the tribes took up farming as their principal means of livelihood instead of hunting, these conflicts would be minimized. Furthermore if the tribes' members became farmers and resided on small plots of land, whites could more easily mine the region's copper. “This copper does you no good,” the Native Americans were told, “and it would be useful for us to make into kettles, buttons, bells, and a great many other things.” [12]A Native American culture based on an agricultural lifestyle would minimize interaction and conflict between Sioux and Chippewa tribal members and also open the land for resource exploitation free from the fear of Native American arms.

The notes taken at Fond du Lac , and subsequently at negotiations a Butte Des Mortes, reinforce the example of Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin and makes clear that not all Native American leaders were willing to follow Waa-Ba-Shaw's model of cooperation with the hope of thus gaining good will. Not all leaders where as direct as Shing-Gaa-Ba-W'OSin in their opposition to Washington 's objectives. Sometimes resistance was indicated by the simple act of not showing up at the appointed place and time. Treaties could not be negotiated if the Native Americans failed to appear. At other times resistance was shown through demands that Washington first offer sufficient tokens of good faith in order to obtain the desired concessions from the Native American leaders. These demands were usually placed in the context of the very real hunger and ill health of the tribe and the need for Washington to address these problems.

The Chippewa leaders present at the Fond du Lac conference in August 1826 expressed a willingness to work with the officials, but also stressed the dire situation that confronted the tribe. They pointed to hunger, especially among the women and children, and drew a clear connection between the effects of this situation and the attitude of the tribe toward the government.

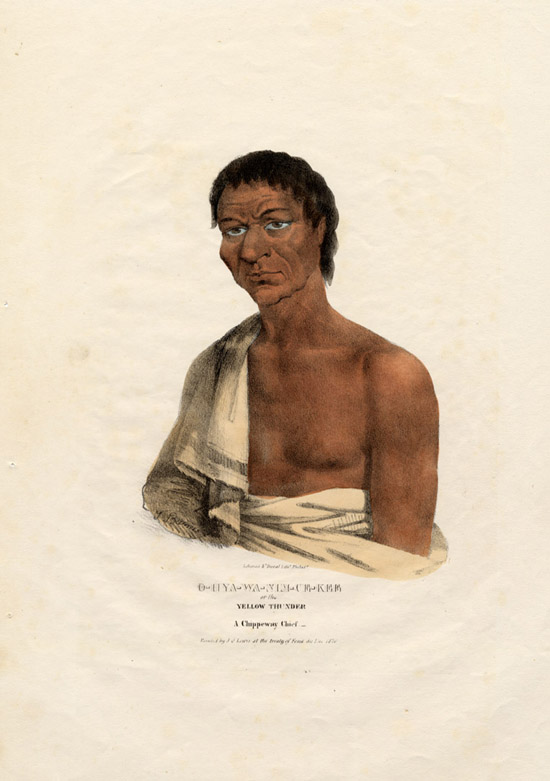

O-Hya-Wa-Nim-Ce-Kee (Yellow Thunder), a Chippewa Chief, explained that more of his band would have attended the council at Fond du Lac , however, “the poverty of my women and children plead for them, and I have left some of my young men to provide for their wants.” [13]A second Chippewa chief, Pe-Schick-Ee (also spelled Peezhickee), appealed to the “Great Fathers,” for provisions because, “Our women and Children are very poor. You have heard it. It need not have been said. You see it.” But Pe-Schick-Ee was not simply asking for humanitarian aid. He stressed that food was necessary for establishing trust between the government and the tribes. Many Native Americans, Pe-Schick-Ee claimed, had departed or altogether avoided the prior conferences because of ill-will. [14]The politically astute Pe-Schick-Ee suggested that the assistance and provisions from the government was necessary not simply because it was the right thing to do but rather because it would aid in repairing a division that was endangering the ability of Washington to sign treaties.[15]

The dire poverty of the Chippewa did not go unacknowledged. In the Fond du Lac treaty language was included obliging the federal government to provide the Chippewa tribe an annuity of $2,000. However, the treaty stipulated that the payment would continue only at the pleasure of Congress. In exchange for the annual payment, the Chippewa had to recognize the authority of the federal government, relinquish trade with other parties, and accept the land boundaries given to them from the federal government. It is difficult to understand when or how the federal government planned to stop payments to the tribe as negotiators conceded that the land allotted to the Chippewa was “unfit for habitation and destitute of game,” thus making the tribe dependent on an annual payment from Congress for survival. [16]

Regardless of the merits of the deal struck in Fond du Lac, negotiating tactics such as failing to appear at the appointed time and place or demanding tokens of good faith from Washington before negotiations could proceed were used by Native American leaders to the frustration of the Euro-American negotiators. To resolve this problem Washington 's commissioners sometimes resorted to personally selecting tribal spokesmen. By appointing representatives who were eager to cooperate commissioners were often successful in negotiating terms to Washington 's liking. The legitimacy of the resulting document was often questionable and frequently failed to be seen as binding by other tribal leaders. For example, the treaty of Fond du Lac explicitly refers to the agreement signed a year earlier at Prairie du Chien and directly raises the question of its legitimacy:

Whereas owing to the remote and dispersed situation of the Chippewas, full deputations of their different bands did not attend at Prairie du Chien, which circumstance, from the loose nature of Indian government, would render the treaty of doubtful obligation, with respect to the bands not represented …

Art. 1: the chiefs and warriors of the Chippewa tribe of Indians hereby fully assent to the treaty concluded in August last at Prairie du Chien, and engage to observe and fulfil the stipulations thereof.

Whether the problem was the “remoteness” of some Chippewa leaders, as the treaty writer assumes, or a subtle way of undermining the treaty by Native Americans, a point Washington's negotiators would likely prefer not to put in writing, the result was that a subsequent treaty was needed to re-ratify a past agreement. This example point out why Native American treaty signers were sometimes appointed by Washington rather than by their own people, but also the limitations of this strategy.

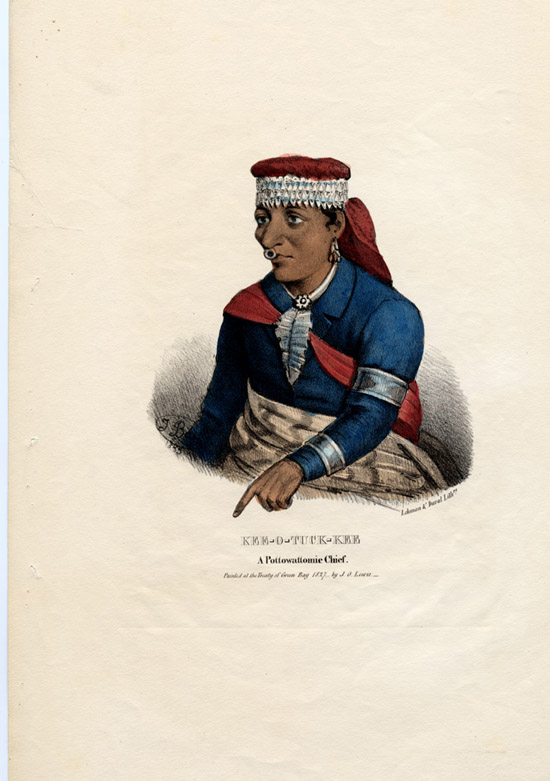

The last treaty negotiation of this period in the Great Lakes occurred at Butte Des Mortes, near Green Bay , in the summer of 1827. As with previous treaties, Butte Des Mortes attempted to establish well-defined tribal boundaries, this time between the Chippewa and the Menomonee. The negotiations at Butte Des Mortes also resulted from increased hostilities between Brothernton Indians and the citizens of Green Bay , and a desire to investigate what must have been a bone-chilling rumor of a pan-Indian uprising near Prairie du Chien. [17] Over thirteen hundred Indians had arrived at Butte Des Mortes by July, and eighteen hundred were in attendance by the time the conference began. [18] Those present included the Menomonee, Winnebagoes, and Chippewa, as well as the New York Iroquois who had previously been displaced. As with the treaties from the previous years, the federal government sought to establish clear geographic parameters for each tribe, require the recognition of the authority of the federal government, and develop an annuity schedule for each of the tribes that would both pacify tribal leaders and forward the work of “civilization.”[19]

The treaty's concluding ceremony unknowingly ended an era for the tribes of the Great Lakes . The Removal Act would become law in three years. Its passage marked the abandonment of the concept of allowing “civilized” Indians to live in close proximity to Euro-American settlement. Instead, official federal policy became one of relocating tribes far away from Euro-American settlement to lands west of the Mississippi River . While relocation would not become law until 1830, official Washington was already advocating voluntary removal in 1827. Thomas McKenney, the head of the BIA, traveled south to meet with tribes there to persuade them to move west of the Mississippi River . [20] Lewis Cass, who was a federal negotiator at many of the Great Lakes treaties, would become Secretary of War in Andrew Jackson's administration. His primary task was the repudiation of the “civilizing” clauses found in many of the treaties he personally had negotiated as territorial governor of Michigan and the implementation of President Jackson's removal policy.

Personal Ornamentation, Weapons and Their Political Importance

Many Native American leaders wore medallions, armbands, or gorgets of political significance. Most important among these pieces of jewelry are the medallions. Known as “peace medals,” these were struck by the federal government and were given to Native Americans of importance, usually at the successful conclusion of treaty negotiations. [21]

The distribution and wearing of peace medallions carried political significance. The British had widely distributed medallions among tribal leaders in the Great Lakes region in the years leading up to the War of 1812. American negotiators interpreted the receiving and wearing of an American peace medal as symbolizing a personal acceptance by a Native American leader of American authority. American negotiators were often at pains to make this point. Anthony Wayne, at the concluding ceremonies of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, the first treaty between the American government and the Indians of the Great Lakes, said:

The medals which I shall have the honor to deliver you, you will consider as presented by the hands of your father, the Fifteen Fires of America. These you will hand down to your children's children, in commemoration of this day – a day in which the United States of America gives peace to you and all your nations, and receives you and them under the protecting wings of the eagle. [22]

A generation later the American negotiators continued to put great stock in the importance of these medals. Thomas McKenney, head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, spoke these words before distributing medals at the conclusion o the Treaty of Fond du Lac in 1826:

Great Chiefs, When you take this great medal, remember you are no more to disobey your great father [the president of the United States ]; no more to advise your warriors to shed blood; nor more to do bad actions. But you are ever after to listen to his counsels and follow them; then this medal will be as a light on your breasts, to which your young men may look and get wisdom.

Warriors, -- When you take this medal, you give the word of a warrior, and not of a dog, to listen to your great chiefs, and mind their words; and if you disobey, and do bad actions, your medal will be a shame to you, and not a badge of honour. [23]

McKenney also went to considerable lengths to be assured that all tokens of British influence were removed. When the son of Pe-Schick-Ee arrived at a treaty negotiation grounds wearing a British medal the chief quickly tried to avoid difficulty by telling McKenney that the medal was his and that the son wore it “for ornament.” McKenney, however, was not willing to allow symbols of British authority to be seen, even if they were mere jewelry. As McKenney relates the story:

I told him [the son] not to think I was hurt with him. I knew he was too good an American to wear the medal as a token of partiality to the British king. He said that was so. Well then, I continued, as you are an American inside, I will make you one outside too. I will give you a medal with the likeness of your great Father in Washington, in exchange for this. He consented.

McKenney ruefully notes however that the young man proved a capable bargainer – demanding and receiving from McKenney an American medal equal in size to the one he possessed before surrendering the British medal to McKenney. [24]

George Washington's administration was the first to strike peace medals. His successors continued the tradition. The medals traditionally bore the image of the president then in office and the coat of arms of the United States. They were originally cast in silver and later silver plate, as well as bronze. They came in three sizes.

Armbands and gorgets were also frequently distributed at the conclusion of treaty negotiations, as well as at other times, as tokens of appreciation. Armbands were, of course, worn around the arm or wrist. Gorgets could be worn singly or in a group around an Indian's neck and chest. In art gorgets look like a necklace when worn singly but appear more like a tie when worn as a group. As with the distinction between British and American peace medals, the source of armbands and gorgets was of political importance. A gorget, for example, stamped with the initials of the Hudson's Bay Company made clear that an Indian had been, and likely still was, in close contact with the British in Canada. Similarly, an armband stamped with an American eagle made the initial impression of a “loyal” Indian under the authority of the “Great Father.”

In the Great Lakes region the decision by an Indian leader to wear, or not wear, various forms of jewelry was not simply a matter of personal style and taste. It was also a statement about loyalties. The symbols Indian leaders wore, or chose not to wear, aligned them unmistakably with the United States, to Britain, and perhaps to their own people.

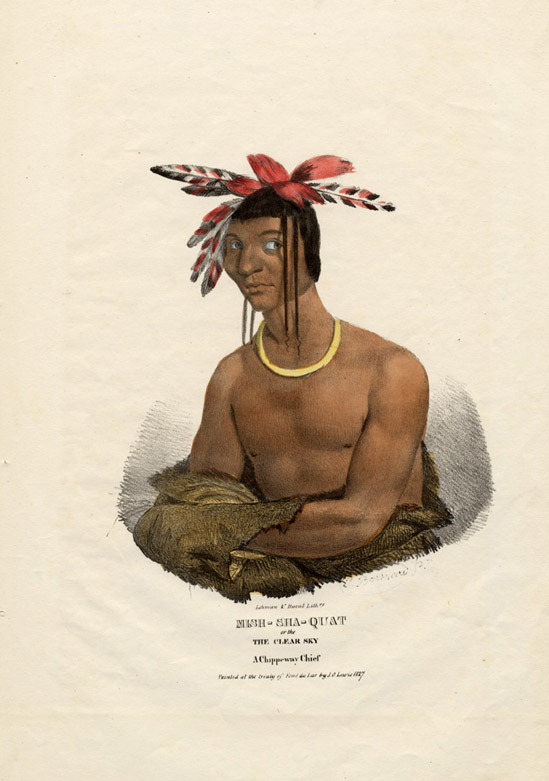

Weapons also played a role in the political reality of the Northwest frontier in the 1820s. The representation of a firearm in a Native American's hands rather than a traditional weapon such as a bow and arrow was a subtle reminder of the past tribal military power and continued potential for armed resistance to Euro-American settlement.

Three weapons from the period are included in the exhibit itself. A U.S. musket manufactured for the state of New York in 1808 is typical of the type of firearm carried by American soldiers in the War of 1812. The 69 caliber weapon was largely patterned on a French musket, the “Charleville,” that was first introduced in 1763.[25]

The British “Brown Bess” musket was the standard weapon of the British army during the War of 1812. The example in the exhibit was manufactured sometime prior to 1790, but British musket design remained remarkably consistent from 1700 and 1830.

The third example is a British Fusil/Fowler manufactured circa 1760. Guns such as these were manufactured for trade. They served as particularly prestigious items and were sought after by many tribal leaders. British officers also often privately purchased and used these better quality muskets, which were effective both in combat and in hunting small game. [26]

Finding the Authentic Voice of Native Americans: A Question of Sources

One of the most difficult problems facing an individual intent on understanding the lives and minds of Native American leaders in the early nineteenth century is the paucity of material, particularly material created by Native Americans. As this catalog demonstrates there are sources that discuss Native Americans from this period. But the vast majority of these sources were created by Euro-Americans and represent aspects of Native American life and culture considered significant by Euro-Americans. For example, the words spoken by Native American leaders quoted in this study are largely recorded in the notes of the negotiators sent from Washington to draft treaties with the Native Americans. The notes may be accurate but the speeches recorded are those that the federal representatives thought important rather than the words the Native American leaders felt mattered most. Ultimately, and tragically, most of the Native Americans who signed the treaties at Prairie du Chien, Fond du Lac, and Butte des Mortes, have become lost to history. For most of the signers, no biographical record remains. Indeed in many cases today we do not even know how to spell their name.

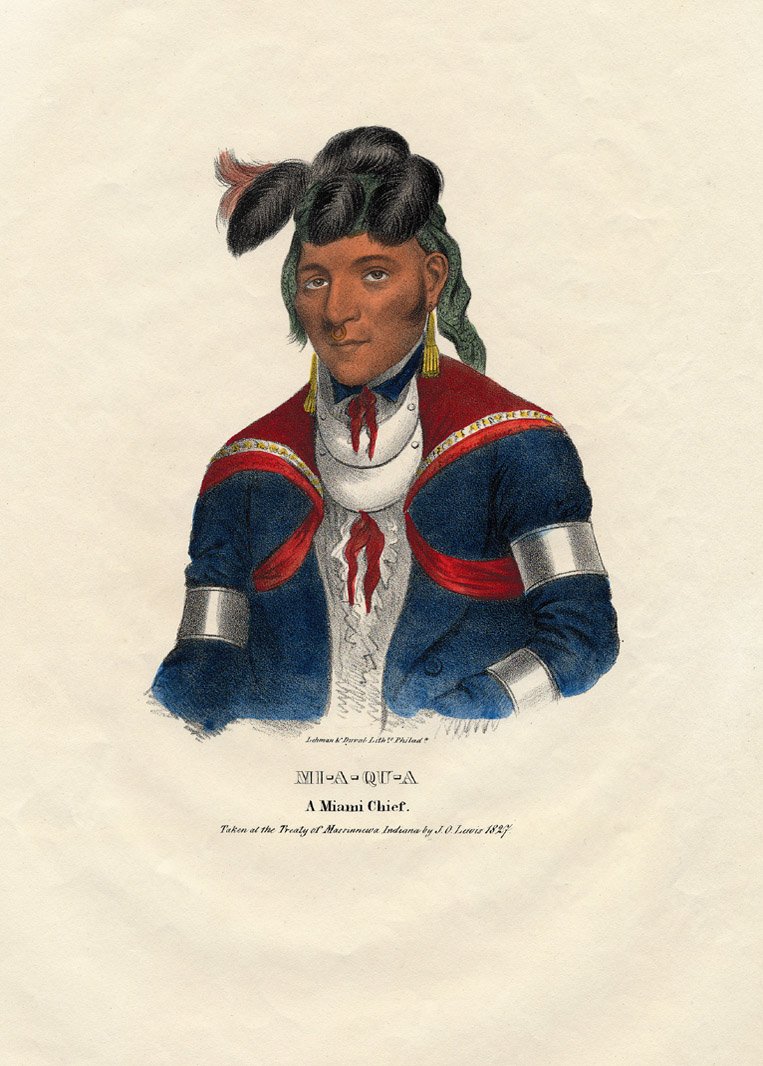

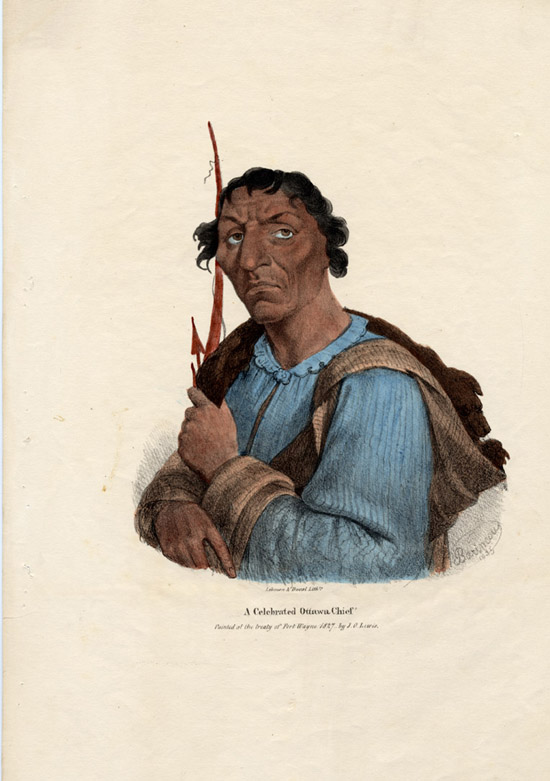

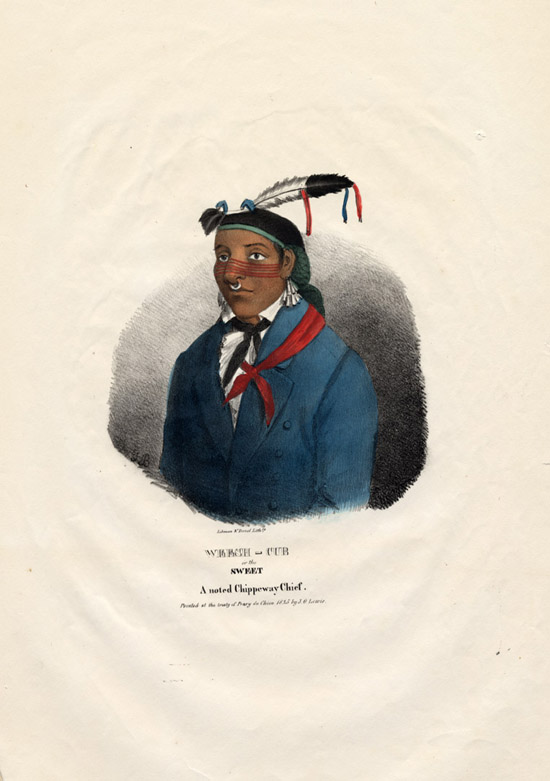

There does exist, however, for the 1820s a unique visual record of the signers that compliments their signature. One member of the federal government's negotiating party in the Great Lakes region was the artist James Otto Lewis (1799-1858). Lewis was commissioned to paint from life Indian leaders. Among others, he attended the proceedings at Prarie du Chien, Fond du Lac, and Butte Des Mortes. Overall Lewis painted more than three hundred portraits of the Native American leaders. A decade after the images were completed Lewis attempted to commercialize his work through a smaller series of approximately seventy published color lithographs.

It is impossible today to reconstruct how Lewis chose the subjects he painted or the paintings he included in his lithographic series. Information about Lewis himself is almost as difficult to locate as information about the Native Americans he painted. Most of what is known about Lewis is found as a footnote in the writing of political figures such as Lewis Cass or Thomas McKenney. These brief and infrequent mentions in the journals, diaries, and memoirs of politicians characterize Lewis as a passive observer, carefully recording his observations of the proceedings and interactions between Native tribes and emissaries of the United States Government. But clearly, Lewis was not a confidant of these political leaders and thus their impressions of him are not drawn from a deep knowledge of the man himself.

Lewis had come to the attention of federal officials after he presented Cass with a portrait of Tens-Qua-Ta-Wa, a Shawnee Indian, known as The Prophet. Cass apparently took a liking to the painting and to Lewis himself. Cass presented the painting to Thomas McKenney, head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and encouraged McKenney to employ Lewis to draw from life the Indian leaders with whom Cass frequently negotiated.

McKenney collected Indian portraits and had created an Indian portrait gallery in the BIA office. The gift by Cass of The Prophet's portrait, as well as words of support shared with McKenney, apparently served their purpose. McKenney commissioned Lewis to create portraits of tribal leaders in the Great Lakes . For this work, Congress authorized nearly $800 in payment to Lewis. [27]

Both Lewis and McKenney realized that there was a profit to be made in selling Indian-related material. In 1827 McKenney published Sketches of the Tour of the Lakes.[28]McKenney's offering, was a traditional book that included a large number of images created by Lewis. Among the illustrations were a few individual portraits, geographical features of the Great Lakes , traditional Native American villages, and other scenes of the cultural environment such as Native American gravesides and Indian canoes. Some of the images in McKenney's book seem to be early drafts of what Lewis would publish a decade later in his own work. Lewis' publication, The North American Aboriginal Port-Folio , was very different than McKenney's. Rather than a book, Lewis offered the public a series of color lithographs, usually portraits.

The glimpse Lewis provides of Native American leaders possesses shortcomings. For example, in his sketch of O-Hya-Wa-Nim-Ce-Kee, a Chippewa Chief, Lewis' portrait rather too conveniently resembles his contemporaries' vision of Native Americans. O-Hya-Wa-Nim-Ce-Kee is dressed only from the waist down and appears stoic and emotionless. Perhaps the chief wished to be portrayed this way but we have only Lewis' drawing rather than some word from the man himself.

Lewis' drawings are also sometimes considered suspect because they present a nationalistic view of the early American republic. As the final ceremonies began at Prairie du Chien on August 19, 1825 , Lewis took up his brush to provide an image of the treaty signing titled, “View of the Great Treaty Held at Prairie du Chien.” In the background the commissioners, undoubtedly Cass and Clark, deliver their final instructions to the tribes. Prominent in the foreground is a large American flag, and flanking the left side are what appear to be a church and the fort, all three of which stand as reminders and symbols—for good or ill—of the increased and continued American expansion westward, not only with regard to people, but also a migration of ideas, values, and cultural attitudes challenging those held by the Native people already inhabiting the region.

In a similar vein, Lewis' one landscape image from Butte Des Mortes depicting the commissioners' arrival projects strands of early American patriotism. The American flag flies atop a hill in the center of the canvas, and one extends from the back of the commissioners' boat. Unlike Prairie du Chien, however, no Native Americans are seen. Only the government fort and the Euro-American settlement and forts greet the commissioners. This artistic representation may foreshadow the pessimistic assessment of the Native American's situation Lewis offered in advertisements for his portfolio:

The poor Indian, an exile from his fatherland, now sleeps beneath the western star. Farther and farther he is driven towards the setting sun; and the shores of the Pacific will soon be vocal with his plaints and moans. The Rocky Mountains now fling their shadows over a dwindling and dying aboriginal race. Desolation pursues them to their mountain retreats, and, like the beasts of prey, they are hunted from the fastnesses in the woods. Darkness and misery, and the deep shadows of death are settling on and encircling their prospects. Wherever they turn, their ears are startled with the terrors of the white man's hand. Civilization is rapidly rolling its terrible billows over their bones and their hunting grounds, and burying in its fathomless bosom the once brave, now fated race. [29]

Lewis' lithographs portray a selected view of Native American life. Despite their flaws, Lewis' images are one of the few views we do have of the period's Native American leaders. And for all their flaws, the lithographs nevertheless do stand in marked contrast to work by other period artists who painted Native Americans. Many contemporary illustrators portrayed Native American's as bloodthirsty savages whose time upon the continent was drawing to a close. At his best Lewis, even if he did not see perfectly, saw something more. 30

A Note on Spellings and Terminology Used by J.O. Lewis and Found in this Catalog

In writing this catalog we have chosen to standardize the spelling of Native American names as they appeared in the captions that accompanied J.O. Lewis lithographs. The decision to do so was not based on a belief that Lewis' choice of spelling was particularly accurate or that he had a particular insight into the Ojibway language. Indeed, Lewis himself could be very inconsistent in spelling. On various lithographs Prairie du Chien is spelled as used in this catalog but alternately represented as “Prarie du Chien” and “Prary du Chien.” The choice to use Lewis spelling of Native American names was made because of the decision to reproduce both Lewis' images and the text which he chose to accompany his images. Because Lewis' captions were to be reproduced it seemed less confusing to use the same spelling of a name when it appeared in the text.

The decision to publish Lewis' captions as they appeared in the nineteenth century also creates the possibility that some readers will be offended by the use of terms common in the 1800s but which today can be interpreted as pejorative. We apologize in

advance to any who take offense at Lewis' language. However Lewis choice of words is important in that it is an additional piece of evidence that helps to evaluate the influence of his Euro-American heritage on the Native American portraits he created.

To delete the words is to lose the evidence. Thus, we have chosen to retain the words, despite their potential to offend.

Footnotes

- Francis Paul Prucha, The Great Father: The United State Government and the American Indians (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 22-24.

- Gregory Evans Dowd, A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745-1815 (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1992), 106.

- Prucha, Great Father, 23; Dowd, Spirited Resistance, 106.

- http://www.lib.cmich.edu/clarke/nativeamericans/treatyrights/greenville.htm

- United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, Ratified Indian Treaties, 1722-1869, “Ratified Treaty No. 139 [Prairie du Chien]” RG 011, National Archives, Washington, DC (microfilm).

- J.O. Lewis, The American Indian Portfolio: an Eyewitness History, 1823-1828. Kent. OH: Volair Limited, 1980. 61-62.

- Speech given by “The Melancholy Indian from the Ontonagon,” Ratified Indian Treaties, “Ratified Treaty No. 145 [ Fond du Lac ]”, 8. RG 011, National Archives (microfilm)

- Speech given by Waa-ba-shaw, Sioux Chief at the Treaty of Prairie du Chien, Ratified Indian Treaties, “Ratified Treaty No. 139 [Prarie du Chien]” ,3. RG 011, National Archives (microfilm)

- Franklyn Curtiss-Wedge, et. al. History of Wabasha County, Minnesota (Winona, MN: H.C. Cooper, Jr. & Co., 1920), chapter 3 and16-20.

- Ibid.

- Article 12 of the Treaty of Prairie du Chien states that a separate treaty with the Chippewa would be held the following year, this was at Fond du Lac.

- Ratified Indian Treaties, “Ratified Treaty No. 145 [ Fond du Lac ]. RG 011, National Archives (microfilm).

- Ibid., 5

- Ibid.

- Some sources suggest that he was the uncle of Indian Agent Henry Schoolcraft's wife.

- Ratified Indian Treaties, “Ratified Treaty No. 145” [ Fond du Lac ]. RG 011, National Archives (microfilm)

- Herman J. Viola, Thomas L. McKenney: Architect of America's Early Indian Policy: 1816-1830 (Chicago: Sage Books, 1974) 155-156

- Ibid., 159-160

- Ratified Indian Treaties, “Ratified Treaty No. 148” [ Butte Des Mortes]. RG 011, national Archives (microfilm).

- Viola, McKenney, 135

- Francis Paul Prucha, Indian Peace Medals in American History (Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1971); Steven Infanti and Andrew Steinitz, The Noble Peace Prizes (Greenville, OH: Treaty of Green Ville Bicentennial Commission, 1990).

- Prucha, Indian Peace Medals, 9.

- Ibid., 45-46

- Ibid., 44-45.

- Flayderman, Norman , Guide to Antique American Firearms…and Their Values , 5 th Edition (Northbrook: DBI Books, 1990). Charleville is a name invented by collectors to describe American muskets patterned after French design. Chareville and Maubeuge were the National Armouries of France.

- The Canadian Journal of Arms Collecting , 6:1.

- Kate E. Levi, “James Otto Lewis,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 4 (1920-21): 357-358; Thomas McKenney, Sketches of a tour to the lakes, of the character and customs of the Chippeway Indians, (Baltimore: F. Lucas, Jr., 1827), xvi

- See Philip R. St. Clair's introduction, “James Otto Lewis: 1799-1858,” in The American Indian Portfolio, An Eyewitness History , 12

- Lewis, North American Aboriginal Portfolio , 15

- Colin G. Calloway, “Painting the Past: Indians in the Art of an Emerging Nation,” in Colin G. Calloway, ed., First Peoples: a Documentary Survey of American Indian History (Boston: Bedford/St. martins, 1999): 205-210.