Exploring the brain’s stress response through fish

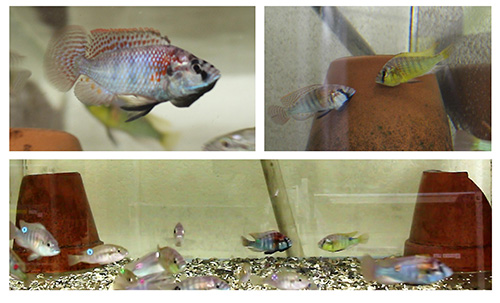

Social hierarchies aren’t just a human thing, they’re everywhere in the animal kingdom, shaping behavior and well-being in surprising ways. At Central Michigan University, Dr. Peter Dijkstra is diving into how social stress tied to these hierarchies affects brain health. His focus? Cichlid fish, a fascinating species known for their complex social structures.

“What we’re really looking at is oxidative stress in the brain,” Dr. Dijkstra explains. “It’s when the balance between harmful free radicals and the body’s ability to neutralize them gets thrown off. That imbalance can lead to serious issues like neurodegenerative diseases and even mental health conditions such as depression.”

Why Cichlid fish?

Cichlids are perfect for this kind of study. Their dominance and social rankings are easy to observe, you can immediately tell who’s on top and who’s at the bottom. That simplicity makes them a go-to species for studying social dynamics.

Cichlids are perfect for this kind of study. Their dominance and social rankings are easy to observe, you can immediately tell who’s on top and who’s at the bottom. That simplicity makes them a go-to species for studying social dynamics.

“These fish are already widely used in animal behavior research, but they’re also becoming a big deal in social neuroscience,” says Dr. Dijkstra. “Most researchers focus on their territorial or reproductive behaviors, but we’re taking it a step further by looking at the physiological toll social stress takes on their brains.”

What’s the research telling us?

Dr. Dijkstra’s lab is breaking new ground by studying oxidative stress across the entire brain in stable social hierarchies—no artificially induced stress here. Early results suggest that subordinate males, the ones lower in the pecking order, experience higher levels of oxidative stress than their dominant counterparts.

Interestingly, these stress levels appear to be tied to specific markers of social dominance, like aggression and reproductive investment. One brain region, the telencephalon, known for regulating social behavior—seems to play a key role.

Why it matters

So, what does this mean for humans? “It’s about understanding how social stress affects brain health,” Dr. Dijkstra explains. “If we can pinpoint these mechanisms in fish, it could eventually help us unravel similar effects in people, especially when it comes to mental health challenges related to chronic stress.”

Hormones like cortisol and androgens may be part of the puzzle. Subordinate males in the study tend to have lower androgen levels and higher cortisol levels, which could make them more vulnerable to oxidative stress. The team plans to dig deeper into how they influence brain health.

A team effort

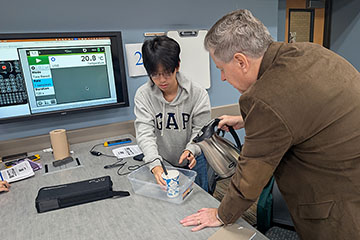

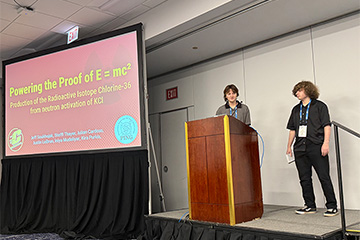

This research thrives on collaboration and student involvement. Honors students Brady Bush and Ashley Harvey contributed through capstone projects, while Earth and Ecosystem Science Ph.D. candidate Robert Fialkowski led much of the lab work. Travis Moore, a former master’s student, conducted the behavioral analysis. Additionally, Dr. Ryan Wong at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, a key collaborator on this National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded project, works closely with Dr. Dijkstra’s team to further this groundbreaking research.

“Getting students involved is a huge part of what makes this work rewarding,” says Dr. Dijkstra. “It’s great to see them making real contributions to such an important project.”

What’s next?

Dr. Dijkstra’s team is just scratching the surface. Future studies will focus on how androgens and cortisol influence oxidative stress, potentially paving the way for insights that could improve brain health in animals and humans alike. The lab will specifically focus on how hormones influence the regulation of oxidative stress in the brain at the genetic level. For now, though, the research highlights just how deeply social dynamics can impact our brains, and what we can learn from a little fish with a big personality.