SAPA experiences forge lifelong connections

CMU alums reflect on time as peer advocates

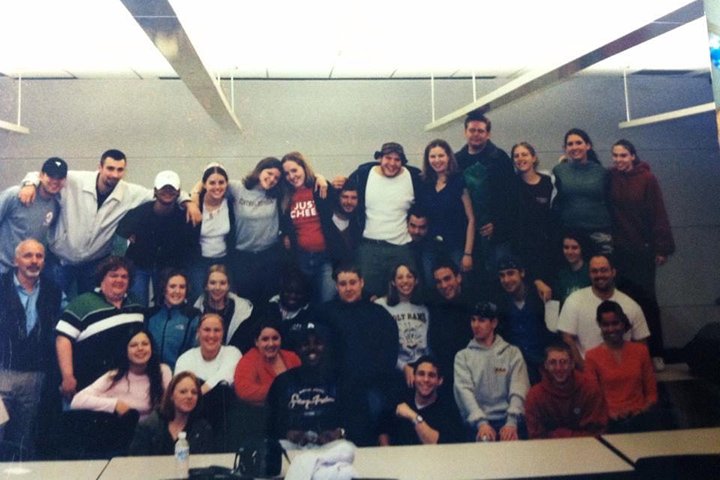

Central Michigan University alums who participated in a unique peer-to-peer sexual aggression advocacy program say the experience lasted far beyond their years on campus.

“We’re fond of saying, ‘Once you’re a Sexual Aggression Peer Advocate, you’re always a SAPA,’” said Megan Varner, director of CMU’s Sexual Aggression Services. Varner started with the organization as a peer advocate in 2007 and was hired into her current role in early 2022.

The organization, which trains student volunteers to provide peer support to survivors of sexual aggression, is celebrating its 25th anniversary in April.

When founded, it made CMU a nationwide leader in addressing sexual aggression, but the program’s story has always been about people.

Survivors at the heart of the SAPA experience

SAPA’s peer advocacy starts with a survivor making contact, usually over the phone but occasionally in person. The peer advocate asks what the survivor needs. Sometimes a survivor wants someone to go with them to the hospital or meet with the police. Usually, they just want someone to listen because they feel they have no one else.

The program operates under strict confidentiality, so the peer advocates don’t usually know what happens to survivors. That doesn’t take away the feeling that a peer has done good by taking that call.

“There are times when you know you’ve made a difference,” said Brooke Oliver-Hempenstall, who joined the organization as a peer advocate from 1998-2001 and served as CMU’s director of Sexual Aggression Services from 2015-2022.

Forging connections that last

If peer advocates practice confidentiality when it comes to survivors, the work fosters tight relationships among members. They develop strong friendships and continue helping the organization even after graduation.

Suzanne Stefanski was introduced to SAPA during her freshman orientation in 1999 and joined the group in 2000. She was the group’s graduate assistant from 2006-08 and worked for two years after her graduation as its first dedicated counselor before leaving CMU.

It’s been more than 20 years since she first joined the group, but she still reaches back to interview prospective peer advocates and returns to help train those selected to serve.

While peer advocates can only help one person at a time by answering phones, they reach many more through outreach programs. Those require SAPAs to spend a lot of time working together on things like the skits modeled on the program’s No Zebras, No Excuses concept.

The “No Zebras” model seeks to empower bystanders to take action when they witness sexual aggression. The idea was inspired by the behavior of zebras, who will sometimes stand and watch passively as predators kill members of their herd.

Peer advocates rehearse the “No Zebras” skits at least twice over the summer and put in two more weekends of training in September. That’s in addition to working the phones and regular meetings throughout the school year.

“For an all-volunteer group, it’s amazing how much time people put into it,” Stefanski said.

That extensive time together helps foster close relationships between members. What they had in common was a desire to help survivors; through that, they formed ties not only to each other but also to CMU.

The nature of the organization also brings together people of diverse academic and social interests, Kubec said. Kubec attended the College of Business Administration; Oliver-Hempenstall and Stefanski have spent their careers in counseling. SAPA was one of a handful of organizations Kubec was involved in while at CMU, including the social fraternity Sigma Alpha Epsilon, but it’s SAPA that stands out.

“SAPA is my main, lasting connection to the university,” he said.

Shaping volunteers’ futures

Oliver-Hempenstall originally enrolled in CMU to study accounting. She joined SAPA during the second year of the peer advocate program. She eventually changed her major to psychology and was headed toward a career in counseling. Since graduation, most of her work has centered on domestic abuse and sexual violence.

In addition to working in CMU’s Sexual Aggression Services, she worked as a domestic abuse advocate in Gaylord and directed River House, a women’s shelter in Grayling. She is currently a counselor in the Gaylord Community Schools.

Other alums, who took a different path following graduation, said the skills they developed through SAPA apply in different ways.

Kubec, who earned undergraduate and graduate degrees in the College of Business Administration says SAPA allowed him to practice interpersonal skills such as empathy and passive listening – skills he uses every day in his job in software sales.

Those soft skills include interpersonal skills like empathy and passive listening. He said he uses them every day in his job.

“I can 100 percent draw a direct line correlating those skills to my time in SAPA,” he said.

Watching society change

The way people talk about sexual aggression has changed a lot in the last 25 years, Kubec said.

SAPA was founded well before the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights 2011 2011 "Dear Colleague" letter on campus sexual aggression and before the #MeToo movement caught fire.

“CMU back in the 90s was making this a priority,” Oliver-Hempenstall said. SAPA was one of the first programs in the nation that allowed peers to advocate for peers.

Peers from the group’s early days have watched society’s approach to the issue change over the past two decades.

Kubec said that when he was a peer advocate, audiences were more skeptical to believe that sexual aggression was common on college campuses; to educate them, SAPA focused on using facts.

These days, he thinks a more effective approach is to acquaint people with stories from survivors, to create a human connection to the problem.

Stefanski said that growing awareness about sexual aggression has brought with it a greater awareness of the trauma it causes; this is reflected not just in society, but also in the frontline workers who deal with it. Police officers, medical workers and even prosecutors are now much more aware of the trauma caused by sexual aggression, Oliver-Hempenstall said.

Programs like SAPA have played a role in changing how people on campus and beyond talk about sexual aggression. Each year that new members of the organization graduate, there are additional people with peer training in the world adding to the rising message, Kubec said.

“It’s cool to witness that change in our culture,” he said.