Indigenous resources in the Clarke Historical Library

November is Native American Heritage Month, which commemorates the history, culture, and contributions of the people who were the original inhabitants of the United States. Central Michigan University honors Native American heritage in collaboration with the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe through educational initiatives, cultural events and speakers, and educational resources for the campus and tribal communities. CMU Libraries celebrate Indigenous peoples through its Native American Heritage collection and the Clarke Historical Library’s corridor displays including nineteenth century Indigenous portraits.

Clarke indigenous resources

The Clarke Historical Library has the most complete collection in the state regarding Michigan's first people. This collection focuses on, but is not limited to, Michigan’s Indigenous peoples from pre-statehood to present.

Notable highlights from the Clarke’s collection include Simon Pokagon’s birch bark books. Simon Pokagon was a prominent member of the of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and a Native American advocate. His books printed on thinly peeled birch bark pay respect to his people who used the medium for many different purposes. One of these birch bark books called The Red Man’s Rebuke (1893) provides a critical perspective of the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. This fair celebrated the 400th anniversary of Cristopher Columbus’s arrival in 1492 in the Americas. Simon Pokagon’s father Leopold was a Potawatomi chief who was one of the negotiators and signers of the 1833 Treaty of Chicago. This treaty was an agreement between the U.S. government and the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi tribes. Like other treaties, one of the tactics used by the U.S. government was to get the chiefs and leaders drunk so they would sign away land. The Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi ceded five million acres of land in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Michigan to the U.S. government, and many were relocated west of the Mississippi River. Leopold abstained from alcohol and successfully resisted removal of his Potawatomi band from Michigan by adopting “civilized” ways of Christianity, landownership, and agriculture. At the 1893 fair, Simon publicly participated in a re-enactment of the 1833 treaty signing and requested his people to “live as white men do.” However, offstage, “The Red Man’s Rebuke” circulated among fairgoers stating Native American lands had been seized by the U.S. government and his people had no spirit to celebrate.

Another notable book in the Clarke’s collection is Diba jimooyung, telling our story : a history of the Saginaw Ojibwe Anishinabek (2005). This book tells the rich history of the Anishinaabe people from their own stories and accounts. The Anishinaabe are the Indigenous peoples of the Great Lakes region, which includes the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi tribes in Michigan. Related to the book is a permanent exhibit at the Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture and Lifeways, which is a cultural museum operated by the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe.

The Clarke has a wealth of other books about Native Americans covering topics such as ethnography, archaeology, education, and local history throughout Michigan. Also noteworthy in the Clarke is its collection of Native American children’s literature. This includes children’s books written in Indigenous languages. One example is

Nishiimeyinaanig (2020), or Our Little Siblings, which is written in Ojibwe and contains 26 stories of animal characters in amusing adventures. The following picture shows Nishiimeyinaanig being read in the Clarke’s annual program of Children’s Books from Around the World. This event celebrates CMU’s language diversity by inviting members of the CMU community to read aloud from the Clarke’s extensive collection of international children’s books.

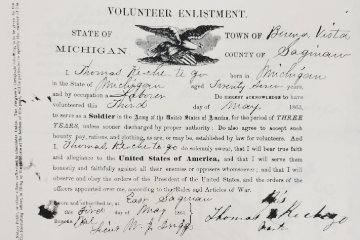

Quita V. Shier’s Company K research collection, documenting Michigan’s First Regiment Sharpshooters, was uniquely composed mainly of Indigenous Michigan soldiers. The collection documents the significance of the unit and the men’s lives and service. Copies of National Archives military service enlistment, pay, invalid status, death or discharge, and/or pension records composed most of the collection. Shier amassed the materials to research her book, Warriors in Mr. Lincoln’s army: Native American soldiers who fought in the Civil War (2018), a copy of which is in the Clarke. To learn more, click on Company K to access the finding aid, or descriptive guide, to the collection.

The 1863 enlistment record (copy) of Sergeant Thomas Kechittigo

The collection of nationally recognized Cherokee poet and CMU professor Carroll Arnett (1927-1997) documents his life and poetry, other Indigenous poets and poetry, the American Indian Movement (AIM), the 1973 Second Wounded Knee, and Dennis Banks, who visited CMU in 1973. In 1970 Arnett was hired to help build a graduate writing program at CMU, where he taught until his death. He served on the CMU President’s Advisory Committee that investigated the “Chippewas” as the University Symbol and helped CMU develop a minor in Native American (Indigenous) Studies. Arnett received a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in Creative Writing in 1974 and published fourteen books of poetry under his birth name, his Cherokee name Gogisgi (Smoke), or a combination of both names. He served his tribe and the greater Indigenous community through his activism and the Indigenous writing community through his mentorship of early-career writers. Indigenous poets and their poetry are a focus of his collection. To learn more, click on Arnett to access the finding aid.

Indigenous bibliography

A good starting point for researchers is the indigenous bibliography. Most researchers start searching for ancestors in the Government Relations section of the bibliography. These extensive records document treaties and treaty rights, military service, annuity payments, removals of Indigenous people from their ancestorial lands, and forced assimilation in U.S. Indian schools. Other sections are: Indigenous children’s literature, Indian Family History, links to related articles, information on the history of the Isabella County Indian Reservation, Native American Treaty Rights, U.S. Indian Schools, and the Olga Denison Anishinaabe Art collection.

Despite the losses of their lands and rights, Indigenous people have endured and revitalized their languages and cultural knowledge. Indigenous research is challenging because many of the records that survive in archives are from a white perspective and were generated to serve white purposes.

Reparative cataloging and description project

Harmful language is part of the historical record and documents how people thought and acted at a specific point in time. Our history is messy and at times was very unpleasant for diverse groups of people. Systems used to describe and catalog library, and archival materials were generated by white people who lacked Indigenous knowledge. The need for reparative cataloging and description projects is now understood to be an ethical priority within the professions of archivists and librarians. Since 2019, CMU Libraries staff have tried to create more respectful subject headings and descriptions. Since they are not Indigenous themselves, they listen and learn from those who are to learn the most appropriate ways to describe Indigenous people. This project is now headed by cataloger Gabriella Stuardi who will blog about it soon.

The Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe Library staff are reclassifying their collections, creating a new classification system based on their Indigenous culture, language, and understanding of information and how it relates to and emanates from them. To learn more about their efforts, listen to the OVERDUE: Weeding Out Oppression in Libraries S3, E4: Maawn Doobiigeng Classification System w/Anne Heidemann & Melissa Isaac podcast.

Visiting the Clarke

Everyone is welcome to visit the Clarke and access our collections in person or via the Clarke’s website. CMU students use the Clarke’s collections to support their coursework. CMU’s Office of Indigenous Affairs recently brought 8th-12th grade Indigenous students attending the North American Indigenous Summer Enrichment Camp (NAISEC) on a group visit to the Clarke.

Please see the Clarke’s website for our hours and contact us if you have any questions.

Here are some additional resources to learn more about Indigenous peoples: The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, and the Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways.

John Berch is the Acquisitions and Cataloging Specialist at the Clarke Historical Library.

Marian Matyn is Archivist in the Clarke Historical Library and Faculty in the CMU Libraries.